How do you fix low cortisol levels (a.k.a. how do you treat “adrenal fatigue”)?

This is a question on the minds of thousands of people every day. The tricky part is that over the last couple decades, there has been an enormous amount of misinformation put online about “adrenal fatigue” that simply has no basis in science.

Table of Contents

In this article (and video/podcast presentation), I’ll be showing you why the concept of “adrenal fatigue” is not supported by the evidence. And in part 2, I’ll show you the real causes of low cortisol levels and how to fix your cortisol levels. (Note: Part 2 can be found here: The real causes of low cortisol levels.)

Download or listen on iTunes

Listen outside iTunes

I present this two-part article for a few important reasons:

- In order to combat the misinformation promoted by so many practitioners around the concept of “adrenal fatigue,” which often misleads people down a typically non-productive path of trying to fix their symptoms by fixing their adrenals (which are, in the vast majority of cases, not the actual cause of their symptoms in the first place.)

- To show that cortisol levels and adrenal dysfunction are NOT the primary causes of fatigue and burnout (and all the other symptoms supposedly caused by “adrenal fatigue” like insomnia, anxiety, depression, etc.).

- To show the real causes of low cortisol levels. (Hint: it’s not that chronic stress wears out your adrenals). And to teach you the simple steps that will allow you to fix your cortisol levels.

First, let’s quickly cover the basic concept of “adrenal fatigue”…

In short, the theory of adrenal fatigue is this:

Chronic stress wears out the adrenal glands (causes “adrenal fatigue”). This results in low cortisol levels, which they claim causes a long list of symptoms.

The proponents of “adrenal fatigue” generally promote a 3-phase model that goes like this:

- Phase 1 – During the initial days and weeks of stress, there is an increase in cortisol levels.

- Phase 2 – With prolonged or chronic stress (either psychological stress or total body stress, i.e. from poor diet, poor sleep, etc.), cortisol levels start to go back down — maybe back into the normal, non-stressed range.

- Phase 3 – As stress becomes even more chronic and goes on for a longer period of time (either psychological stress or total body stress, i.e. from poor diet, poor sleep, etc.), the adrenals start to “fatigue” and not be able to produce enough cortisol to keep up with the body’s needs. At this point, the low cortisol levels manifest in various symptoms (e.g. fatigue, anxiety, sleep troubles, poor blood sugar regulation, etc.).

This theory is reasonably logical and seems to make some sense. That’s why there are tens of thousands of people that have subscribed to it, teach it, and claim to diagnose people with “adrenal fatigue.”

The general gist of what articles on adrenal fatigue claim is that chronic stress eventually wears out your adrenal glands, and this results in low cortisol levels, which then causes symptoms (fatigue, anxiety, difficulty sleeping, etc.). Then they recommend that you adopt strategies to combat this chronic stress and use strategies to support your adrenal gland health – e.g. do rest/relaxation, do meditation/mindfulness practices, get more sleep, support your adrenal glands ability to produce cortisol with vitamin C and B vitamins, take adrenal glandulars or hydrocortisone (to boost your cortisol levels), etc.

Again, the basic idea is:

- Stress wears out the adrenals

- This state of “adrenal fatigue” and low cortisol levels then cause various symptoms (low energy levels, sleep problems, etc.).

It sounds reasonable enough. But there is one enormous problem with this theory that very few people are aware of (because discovering it requires spending hundreds of hours delving into the scientific research)…

It’s simply not supported by the scientific evidence.

(Side note: Before we continue, it’s worth noting that there are legitimate, accepted and real medical conditions that involve actual adrenal dysfunction like Addison’s disease. I am certainly not claiming that Addison’s disease is not real. It is, of course. But it is entirely unrelated to the concept of adrenal fatigue. If you wish to understand the difference between these two things, click the popup box below. But these are technical details not necessary to understand for most readers. So feel free to skip the popup box below and carry on reading the main article below.)

Differentiating True Adrenal Insufficiency and Addison’s Disease from The Body Intentionally Lowering Cortisol Levels

We also need to define exactly what is meant by “low cortisol.”

People are often diagnosed with “adrenal fatigue” and told they have low cortisol levels due to their adrenals not being able to produce enough cortisol.

It’s important to understand that in these cases, it’s almost always a SMALL decrease in cortisol levels, and specifically lower cortisol levels during the morning rise in cortisol levels and NOT low 24-hour output of cortisol.

As explained previously, even in cases where morning cortisol levels are low, 24-hour output of cortisol is typically normal (showing that there is no deficit in cortisol production.)

Moreover, we’re talking about SMALL differences in cortisol levels – nothing like what’s seen in conditions where this is a true inability of the adrenals to produce enough cortisol.

As a way to illustrate this essential point from an endocrinology expert’s perspective, consider Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), which is genuinely associated with lower cortisol levels. Here is one expert, Dr. Rachel Yehuda – a neuroscientist and the director of the traumatic stress studies at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, a scientist who has played a major role in advancing our scientific understanding of the role of cortisol in PTSD — commenting on this subject:

“When we say ‘low cortisol levels,’ an endocrinologist would cringe. In PTSD, cortisol levels are not lower than normal range. They are significantly lower on average compared to persons without PTSD, but the levels themselves are not abnormal. The cortisol levels in PTSD do not suggest that the adrenal gland is broken in any way or not releasing cortisol…We are not talking about an endocrine problem. We are talking about a tendency to be at the lower end which is within normal variability.”

I.e. It’s possible (and common) to have lower morning cortisol levels, but not actually have any problem with your adrenal gland health/function. This pattern of lower morning cortisol levels is a totally different thing from true “adrenal insufficiency” or Addison’s Disease – which is a real condition where the adrenals cannot produce enough cortisol.

But let me be clear that real cortisol abnormalities (and true problems at the adrenal level) can occur.

We have overt recognized diseases like Cushing’s Syndrome and Addison’s Disease, which are serious medical conditions that are real types of adrenal dysfunction. Addison’s Disease is a true inability of the adrenals to produce enough cortisol. There is no debate that these conditions do exist.

There is also a very small subset of people with a genetic variation/mutation in a gene called CYP21a2 that leads to a deficiency of a key enzyme (21-hydroxylase) that is involved in with cortisol synthesis.

But again, let me be clear that Addison’s disease (and/or the genetic issue mentioned above) are NOT what is going on in the majority of people who have been diagnosed with “adrenal fatigue” or suspect they have “adrenal fatigue.” The pattern of low morning cortisol levels (that some people think means “adrenal fatigue”) typically has NOTHING to do with any actual adrenal dysfunction or “adrenal burnout.” I.e. it’s not because your adrenals are incapable of producing enough cortisol, as is claimed by “adrenal fatigue” proponents.

So how do you know if you have Addison’s Disease – i.e. a true inability of your adrenals to produce enough cortisol?

Simple: ACTH (the hormone produced by your pituitary that stimulates your adrenals to secrete cortisol) will be HIGH, while cortisol levels are LOW (typically extremely low, at all times of day).

(Side note: Sometimes it’s more complex than this. It’s also technically possible to have very low ACTH, if there is a problem with the pituitary gland – this is called secondary adrenal insufficiency. But high ACTH – primary adrenal insufficiency – is the more common form of Addison’s Disease.)

That pattern of high ACTH and low cortisol means that the brain is screaming at the adrenals “produce more cortisol!” but the adrenals can’t actually produce the cortisol. (Also, importantly, 24-hour total cortisol levels will virtually always be low in these cases, not just morning cortisol levels.) That’s how we can know if there is truly at problem at the level of the adrenal glands’ ability to produce enough cortisol.

The studies have tested adrenal/HPA axis function in Burnout Syndrome and Stress-Related Exhaustion do NOT find a pattern of low cortisol levels and high ACTH levels. So we know that these conditions are not caused by an inability to produce cortisol in the adrenals (as is legitimately the case with Addison’s Disease.)

(Note: If you have been diagnosed with Addison’s disease, this article is not intended for you. This article is intended for people who have been diagnosed with “adrenal fatigue” or believe that they have “adrenal fatigue.” If you have severely low cortisol levels at all times of day and/or high ACTH, more than likely, you’ve already been diagnosed with Addison’s Disease and are receiving cortisone-based medication for it – i.e. to keep your cortisol levels in the normal range in spite of your adrenals’ inability to produce enough.)

Let me repeat this for emphasis: This pattern (of high ACTH and low 24-hour cortisol levels) is NOT what is going on in people with the vast majority of people who have low morning cortisol levels or people with Burnout Syndrome or Stress-Related Exhaustion Disorder.

KEY POINTS:

- Addison’s disease is a real condition that involves true adrenal dysfunction. But this is an entirely different condition that has nothing to do with the concept of “adrenal fatigue.” It is extremely misleading and inaccurate to conflate these two concepts (as many advocates of “adrenal fatigue” often do.)

- As you’ll see in this article, the overall body of research makes it clear that Burnout Syndrome or Stress-Related Exhaustion are not caused by (or even related to) any deficit in the adrenal glands ability to produce cortisol.

The Big Problem: The Entire Theory Of "Adrenal Fatigue" Is Simply Not Supported By The Scientific Evidence

If you really want to fix your symptoms of fatigue or stress-related exhaustion, read on …

Here’s a quick overview of what you’re about to discover in this article:

- Chronic stress is NOT reliably associated with low cortisol levels. Chronic stress is most frequently associated with high cortisol levels or even normal cortisol levels.

- Low cortisol levels are NOT reliably associated with stress-related burnout/fatigue/exhaustion (i.e. the symptoms claimed to be caused by “adrenal fatigue.”)

- The solution to the symptoms that are claimed to be caused by “adrenal fatigue” is NOT to “fix your adrenals” or fix your cortisol levels. The solution to these symptoms is NOT simply to take supplements that support adrenal health or replace adrenal hormones (like with adrenal glandulars or hydrocortisone). (We’ll cover this in Part 2.)

- The real factors that cause low morning cortisol levels (95%+ of the time) and how to fix low morning cortisol levels. (We’ll cover this in Part 2).

In short, you’re about to learn why the “adrenal fatigue” theory is NOT supported by the scientific evidence, and why you shouldn’t waste your time trying to fix your symptoms by fix your “adrenal fatigue.”

How We’re Going To Assess The Validity of The “Adrenal Fatigue” Theory

My goal in this analysis of the research is to systematically dismantle and debunk the theory of “adrenal fatigue.” (And to do so in a way that makes it plainly obvious and irrefutable that adrenal/cortisol abnormalities are not actually the real cause of the symptoms/conditions that many people say are the result of “adrenal fatigue.”

Here’s how we can assess the validity of the theory of “adrenal fatigue” (and the basic concept that there is a reliable pattern of adrenal deterioration associated with chronic stress/disease?

Here’s how: We systematically analyze these layers of evidence:

- Evidence that has analyzed cortisol levels in people under various kinds of chronic stressors, and assess if there is a reliable pattern of cortisol levels in people in chronic stress.

- Evidence that has analyzed cortisol levels in people with various kinds of chronic diseases(which is often considered a type of “metabolic stress”), and assess if there is a reliable pattern of cortisol levels in people in chronic disease states.

- Evidence that has analyzed cortisol levels in people with Burnout Syndrome and Stress-Related Exhaustion Disorder(conditions that are basically synonymous with the general idea of “adrenal fatigue”), and assess if there is a reliable pattern of cortisol levels in people with stress-related burnout/exhaustion.

- Finally, if no clear pattern of low cortisol levels exists in people under chronic stress, with chronic disease or in stress-related burnout/exhaustion, then we need to analyze the evidence that can explain why some people show up on cortisol saliva tests as having low levels of cortisol.

With this in mind, let’s now dig into these layers of evidence (scientific research) to discover whether or not the theory of “adrenal fatigue” is congruent with the evidence…

Does Chronic Stress Cause Low Cortisol Levels?

The central concept of the adrenal fatigue theory is that chronic stress wears down the adrenals, eventually rendering them unable to produce enough cortisol to meet the body’s needs, and then you get symptoms (fatigue, depression, insomnia, anxiety, etc.)

Here’s the problem: If you actually look to the scientific literature that has assessed cortisol levels in people suffering from chronic stress, there is no clear relationship at all.

If anything, the overall literature shows that both acute AND chronic stress are characterized by HIGHER (not low) cortisol levels.

There are dozens of studies that have found higher cortisol levels in people under chronic stress, and there is no pattern whatsoever that emerges from these studies that shows that chronic stress reliably leads to “adrenal fatigue” and low cortisol levels.

Let’s take a comprehensive look at many different types of chronic stressors and their link with cortisol levels:

- CHRONIC PSYCHOLOGICAL/EMOTIONAL STRESS: One of the best studies that has examined this question – published in the journal Psychoneuroimmunology – concluded “In line with several recent studies, the present findings further support the view that the cortisol awakening responses is consistently enhanced [higher] under chronic stress conditions.”[1] That means that research consistently finds higher morning cortisol levels in people suffering from chronic stress. The authors also review numerous other studies on this subject and note that studies are very consistent in showing chronic stress is associated with high cortisol levels (not low) cortisol levels. They said “…similar relations between chronic stress…and the cortisol awakening response could be demonstrated in two further recent studies. Schulz et al. reported an increased free cortisol secretion after awakening in subjects perceiving high work overload while Wust et al. found a similar relation to social stress in a sample of 383 healthy adults. …an association between prolonged job strain and early morning cortisol elevations was observed by Steptoe et al. Thus the association between enhanced cortisol awakening responses [higher morning cortisol] and high chronic stress can be regarded as rather consistent.”[3]

- CHRONIC STRESS FROM UNEMPLOYMENT: Another study examining cortisol levels in chronic stress associated with unemployment found no difference in 24-hour output of cortisol between chronically stressed unemployed people vs. employed people. And they also found higher (not lower) morning cortisol levels.[4]

- CHRONIC STRESS FROM WORK OVERLOAD: One key study looking at people chronically stressed due to work overload vs. unstressed individuals found that chronically stressed persons had slightly higher (not lower) morning cortisol levels.[5]

- CHRONIC STRESS FROM WORK STRESS (EFFORT/REWARD IMBALANCE): Another key 2013 study titled “Is there an association between work stress and diurnal cortisol levels?” examined the extent to which people had a chronic imbalance of effort to reward at work.[6] Here are the results showing virtually no difference in cortisol levels between the groups with high work stress vs. low work stress, and perfectly normal cortisol levels in the group with high work stress. Another study looked at a high-stress job (emergency room physicians) and looked to see if there was any correlation between the extent to which doctors reported severe job stress and their cortisol levels. They found no relationship between job stress and cortisol levels.

Another fascinating study looking at specific variables within work environments found that people in low stress (not high stress) jobs actually had lower morning cortisol levels compared to people in high strain jobs(and no differences in cortisol at other times of day).[7] - CHRONIC METABOLIC STRESS FROM CIGARETTE SMOKING. Another perfect example of a chronic stressor is being a chronic cigarette smoker. No doubt that smoking cigarettes is a profound chronic metabolic stressor. So chronic cigarette smoking should be a factor that drives low cortisol levels. But it doesn’t! Smoking lots of cigarettes each day doesn’t make you any more likely to have low cortisol levels. In fact, the biggest analyses that have been done show that if anything, chronic cigarette smoking is associated with higher (not lower) morning cortisol levels.[8] But many studies find perfectly normal cortisol levels. (And that’s not even controlling for the fact that most smokers also tend to be less health conscious people and also generally have many other poor lifestyle habits.)

- CHRONIC METABOLIC STRESS FROM HEAVY ALCOHOL DRINKING. Again, consistently associated with slightly elevated cortisol. The more alcohol one consumes on a daily basis, the higher their cortisol levels get. There is no point at which heavy drinking is associated with lower cortisol levels or anything resembling “adrenal fatigue.” [28]

- ATHLETES OVEREXERCISING STRESS (OVERTRAINING SYNDROME). A 2017 systematic review (the highest level of scientific evidence) of the hormonal aspects of “overtraining syndrome” – i.e. chronically over-exercising beyond the body’s ability to recover. They reviewed 6 studies that examined baseline cortisol levels in athletes with overtraining syndrome vs. normal healthy athletes (who were not overtraining). One of those studies showed slightly higher cortisol levels, one showed slightly lower cortisol levels, and 4 of the 6 studies (66.7% of the studies) showed perfectly normal cortisol levels. [9] Researchers noted that baseline levels of cortisol (and most other hormones) were not altered in athletes in chronic overtraining and concluded that if cortisol (and other hormone) levels are normal, then changes in levels of these hormones almost certainly cannot be used as an explanation of the “cause” of the symptoms of overtraining. In their words: “Notably, hormonal changes in [overtraining syndrome] are probably not triggers of these disorders.”[10]

- CHRONIC PAIN (PHYSICAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL STRESS). Another study looked at cortisol levels in people with long-term chronic pain. Importantly, chronic pain is a near perfect thing to study to assess whether chronic stress leads to cortisol reductions because it causes both physiological stress directly to the cells as well as psychological stress as a person is “stressed out” by being constantly in pain. So does chronic pain lead to low cortisol levels. Here is one typical graph you find in the research on this subject, from a study specifically looking at cortisol responses to chronic back pain. The research consistently finds that long-term stress from chronic pain is associated with slightly higher (not lower) cortisol levels.[11],[12],[13]

Finally, a comprehensive review of the scientific literature on cortisol levels across a broad range of chronic stressors concluded that total cortisol production over the morning is slightly increased on average in people due to almost all types of chronic life stressors.[14]

An important point that needs emphasis: Even when studies do find some difference in cortisol levels (either higher or lower), it’s almost always a very small difference and is almost always still well within the range of normal cortisol levels – i.e. NOT a large difference in cortisol that would indicate that the adrenals aren’t able to produce enough cortisol. We’re talking about slight differences in cortisol levels relative to normal healthy people. These studies are NOT finding anything remotely similar to true “adrenal insufficiency”/Addison’s disease (real conditions with adrenal abnormalities), and when directly tested, there is almost never any actual deficit in the ability of the adrenal glands to produce enough cortisol.

There is virtually no research in existence that suggests that chronic stress of any kind ever results in “adrenal fatigue” (wearing out the adrenals so they genuinely are unable to produce enough cortisol).

KEY POINTS:

- There is absolutely no clear pattern of chronic stress being associated with low cortisol levels.

- Overall, most chronic stressors are associated with only very minor differences in cortisol (usually slightly higher, not lower, cortisol) and many studies find no abnormalities at all in cortisol levels.

- There are lots of chronic stressors which either do not disturb cortisol levels at all or slightly increase cortisol levels (even when those chronic stressors persist for years or decades, like smoking or chronic anxiety) and virtually no examples of any stressor that is reliably associated with low cortisol levels.

In summary, the evidence does not support the theory that chronic stress (whether psychological, physical, metabolic, or chemical stress, or some combination) reliably leads to “adrenal burnout” and low cortisol levels. Most studies looking at cortisol levels in various kinds of chronic stress show slightly higher or normal cortisol levels.

Do Other Conditions/Diseases Cause Low Cortisol/“Adrenal Fatigue”?

What about other conditions that could be characterized as “chronic stress” or “metabolic stress” (sometimes also called “total body load” or “allostatic load”) – things like depression, heart disease, obesity, anxiety, PTSD, schizophrenia, diabetes, etc.? Certainly chronic diseases like diabetes or heart disease or metabolic syndrome are acting as chronic 24-7 stressors on the body.

So do they result in “adrenal burnout” and low cortisol levels?

Answer: No. Many chronic diseases and health conditions – even chronic debilitating illnesses – show perfectly normal cortisol levels, or only minor differences from normal.

Also, cortisol levels vary wildly from one condition to the next. There is no general pattern that emerges in chronic disease, where chronic illness leads to low cortisol levels.

For example:

- Metabolic Syndrome – Among people who have had metabolic syndrome for over 5 years (i.e. long-term chronic metabolic stress), they had no differences in cortisol levels compared to normal healthy people.[12]

- Heart disease – Associated with slightly increased cortisol levels or normal cortisol levels.[14]

- Diabetes — No differences in morning cortisol levels and slightly elevated evening cortisol levels compared to normal healthy people.[i]

- Past trauma/PTSD – Associated with slightly decreased morning cortisol levels. (This is one of very few examples which has a clear association with slightly lower morning cortisol levels. Importantly, there is no actual indication of any inability of the adrenals to produce enough cortisol. This is explained here by PTSD expert Dr. Rachel Yehuda.)

- Depression – Some subtypes of depression are associated with increased cortisol and other subtypes with decreased morning cortisol. Inconsistent findings among many studies. Long-term cortisol levels have also been tracked in people with major depressive disorder. The cortisol findings are all over the place, with no consistent relationship between symptoms and cortisol levels. “Approximately 50% of patients with major depressive disorder exhibit elevated cortisol secretion throughout the normal 24 h circadian cycle. The remainder may be eucortisolaemic [normal cortisol levels], or may even have lowered baseline cortisol secretion.”[13]

- Anxiety Disorders – Typically associated with increased cortisol levels or normal cortisol levels.

- Schizophrenia – Overall, most research either shows increased cortisol levels or normal cortisol levels. There are inconsistent findings.[15],[16],[17]

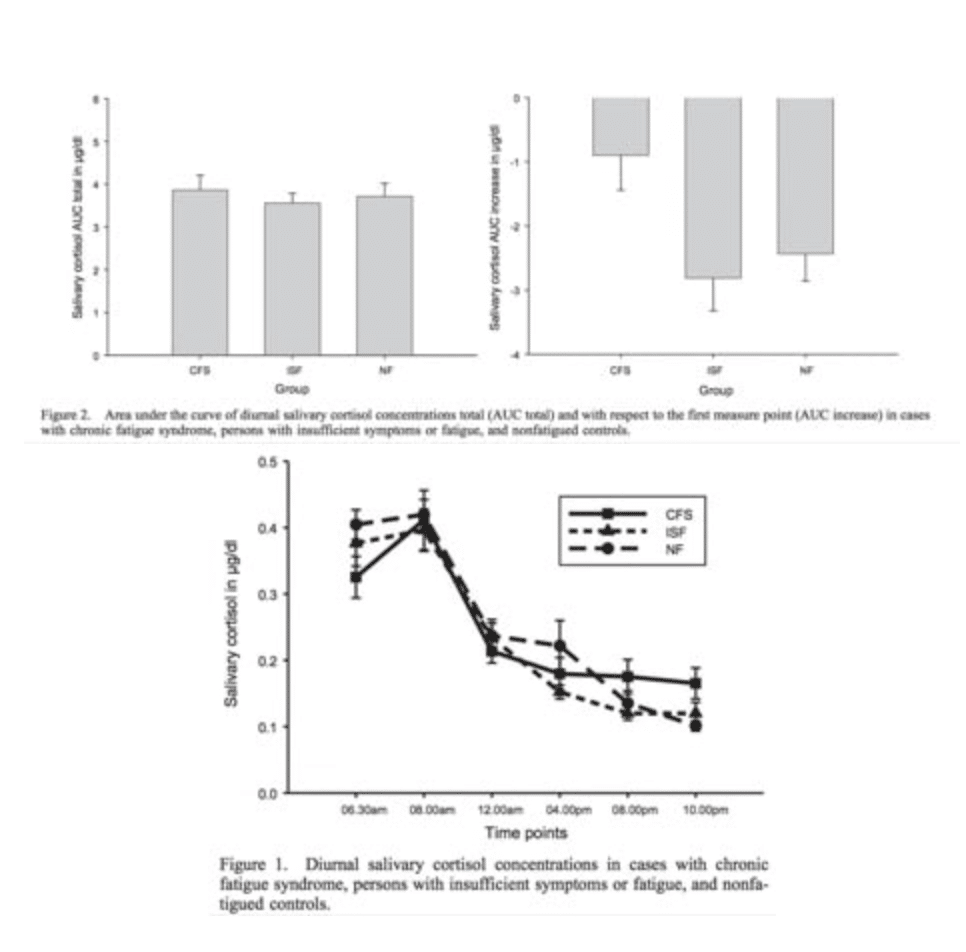

- Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Fibromyalgia – Several studies show slightly higher cortisol, some show lower and some show no difference. (A comprehensive review of the contradictory research on CFS, FM and cortisol can be found here). Here’s one example where the cortisol levels were charted in people with CFS vs. people with mild fatigue vs. healthy people with no symptoms:

- As you can see, there is no clear association between fatigue or chronic fatigue syndrome and low cortisol levels.[29] The total cortisol produced over the day is almost exactly the same as the healthy non-fatigued people.

- Bipolar disorder – Associated with increased cortisol levels, if anything.[18]

- Hashimoto’s hypothyroidism – Hashimoto’s hypothyroidism is typically associated with increased cortisol levels (contrary to many claims that it is associated with low adrenal output).[19],[20]

- Alzheimer’s Disease – No difference in cortisol levels between those with it vs. normal healthy people of the same age.[21]

As you can see, there is absolutely no clear relationship of cortisol levels to virtually all chronic diseases. Different diseases are associated with totally different cortisol abnormalities. Moreover, it is very often the case that even within the same disease/condition, different studies often find contradictory results – i.e. some studies find slightly higher cortisol, others find slightly lower cortisol, and others find perfectly normal cortisol levels correspond to that same condition. Also, note that differences are typically small. And in none of these cases is there any research suggesting that any of these diseases are associated with any inability of the adrenals to produce enough cortisol.

Simply put, it’s abundantly clear that there is no reliable relationship between chronic disease and low cortisol levels (or anything resembling any kind of deficit in the ability of the adrenals to produce enough cortisol).

In summary, there the vast majority of chronic stressors (and chronic diseases – i.e. chronic metabolic stressors) are generally associated with either slightly increased cortisol levels or normal cortisol levels that are indistinguishable from normal healthy people. There are virtually no examples at all where any chronic stressor or chronic disease process reliably leads to any low cortisol pattern that resembles anything we might expect based on the “adrenal fatigue” theory.

Moreover, these differences are typically very small, and it’s common to find perfectly normal cortisol levels in individuals with all of these chronic stressors and chronic diseases.

Now, is it possible that there can be cortisol abnormalities with extreme and decades-long chronic stress/illness? Sure. Every system in the body can potentially show signs of dysfunction as health severely deteriorates. But even here, the research doesn’t support that even severe decades-long chronic illnesses are reliably associated with low cortisol levels.

In short, the science is clear that neither chronic stress or even overt chronic disease has any reliable connection to low cortisol levels or “adrenal fatigue.”

The claim that there are 3 “phases of adrenal fatigue” that happen with chronic stress, or any distinct phase of “adrenal burnout” is simply not supportable by the evidence.

Are Low Cortisol Levels Linked By Stress-Related Exhaustion or Fatigue? (Debunking "Adrenal Fatigue")

Now let’s look at the most important subset of evidence. Let’s specifically look at the research directly testing the “adrenal fatigue” theory by examining the studies on cortisol levels in people with Burnout Syndrome or Stress-Related Exhaustion Disorder (basically synonymous concepts to “adrenal fatigue”).

One of the problems with looking at the research on “adrenal fatigue” is that, well… there isn’t any research!

I’m not exaggerating. Go search for yourself on Pubmed.com (like Google for scientific research). There are virtually no studies in existence on the topic of adrenal fatigue.

Fortunately, there is an easy way around this. There are a couple of conditions that are basically synonymous with the general idea of “adrenal fatigue” – Burnout Syndrome and Stress-Related Exhaustion Disorder.

These conditions are where chronic stress turns into symptoms – they are characterized by the same symptoms claimed for “adrenal fatigue.” The only differences are that:

- There is actually research on them (unlike adrenal fatigue).

- These conditions make no claims that it is specifically one system/hormone of the body responsible for these symptoms (whereas “adrenal fatigue” claims that the reason stress manifests in symptoms is due to “burnout” of the adrenal glands).

There are dozens of studies that have examined cortisol levels in those with Burnout Syndrome or Stress Related Exhaustion Disorder, and compared their cortisol levels against normal healthy people without chronic stress or any of these symptoms. (Note: This research has been done with the specific purpose of trying to find whether or not cortisol abnormalities are responsible for the symptoms in these conditions).

What do these studies consistently find?

- A few find slightly higher cortisol levels…

- A few find slightly lower cortisol levels…

- And the majority of them find no difference at all in cortisol levels between people with burnout syndrome or stress-related exhaustion disorder vs. normal healthy people without any chronic stress.

Importantly, most people with burnout syndrome and stress-related exhaustion disorder have perfectly NORMAL cortisol levels that are indistinguishable from normal healthy people who don’t have symptoms/chronic stress.

This is a critically important point, because if it’s possible to have these symptoms with no adrenal abnormalities (and indeed, most people do!), then we can say definitively that the symptoms are not being caused by cortisol/adrenal issues.

I.e. Contrary to the “adrenal fatigue” theory, the scientific evidence definitively proves that the symptoms in these conditions are NOT actually caused by low cortisol levels.

If you want to see all the research for yourself, go look through my detailed analysis of the research for yourself. (There are 79 studies in that article, most which have screenshots of the cortisol findings.)

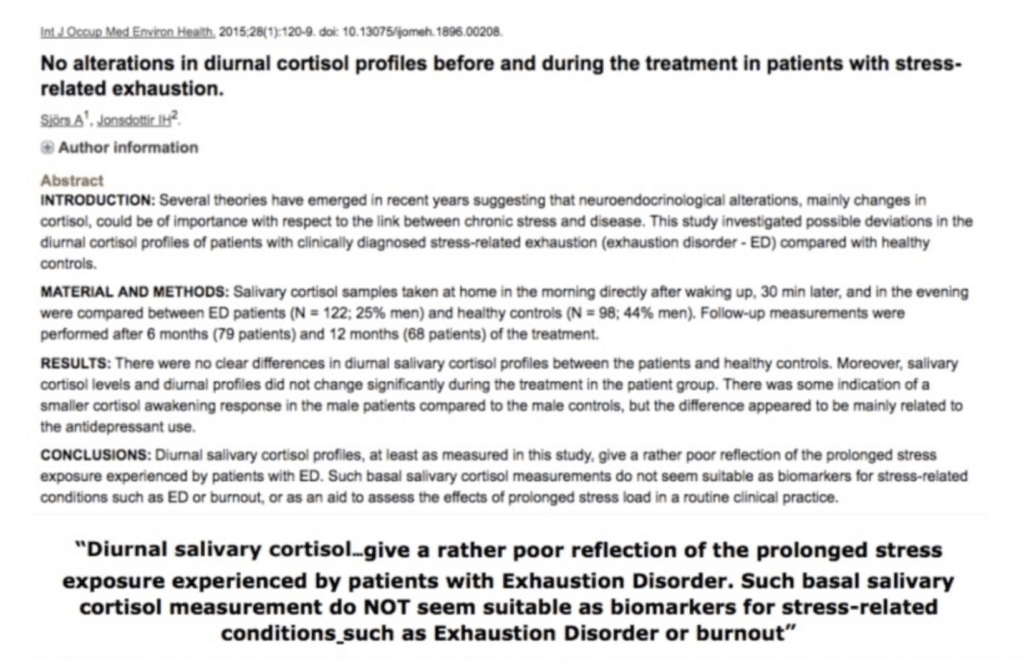

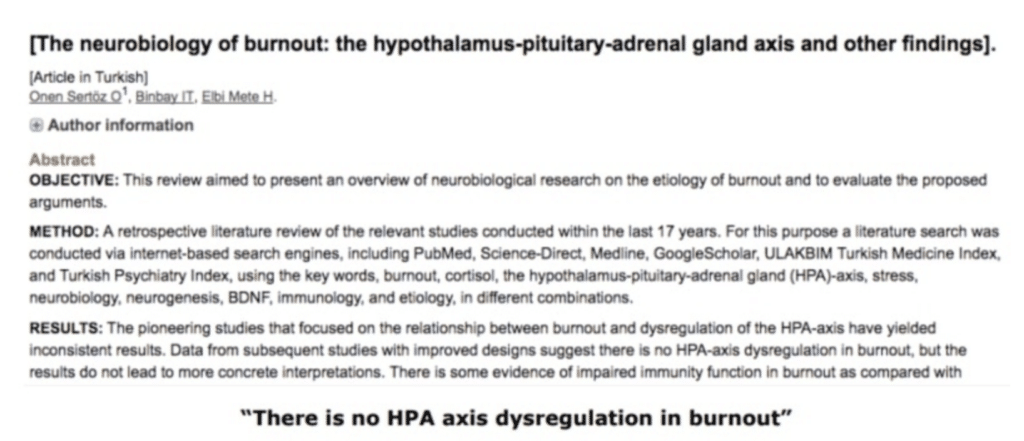

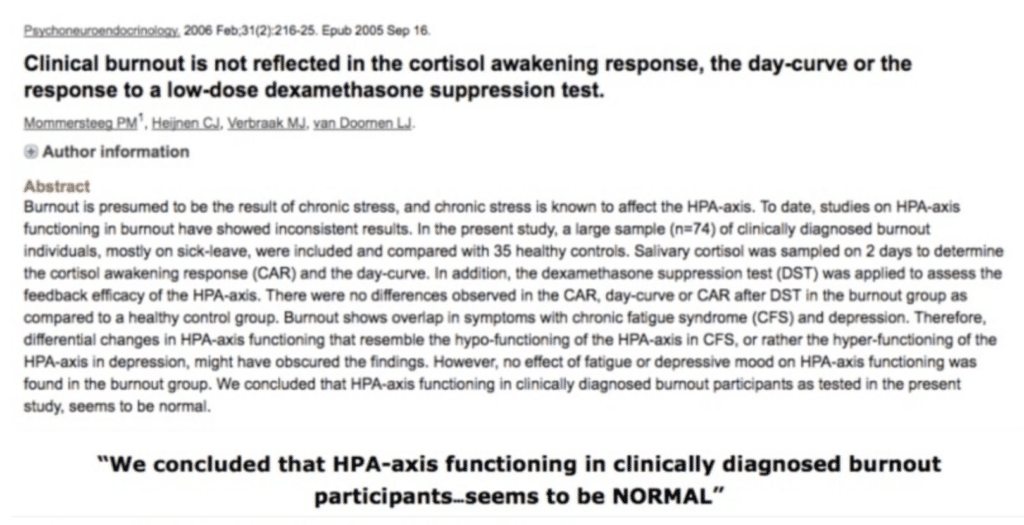

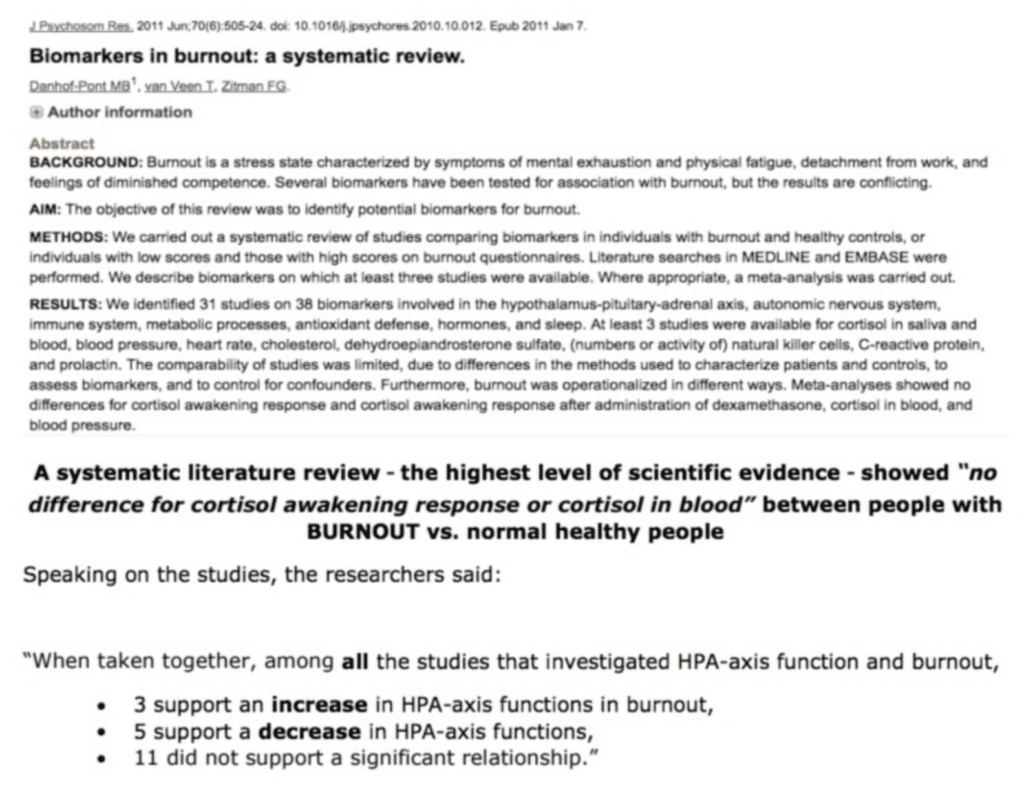

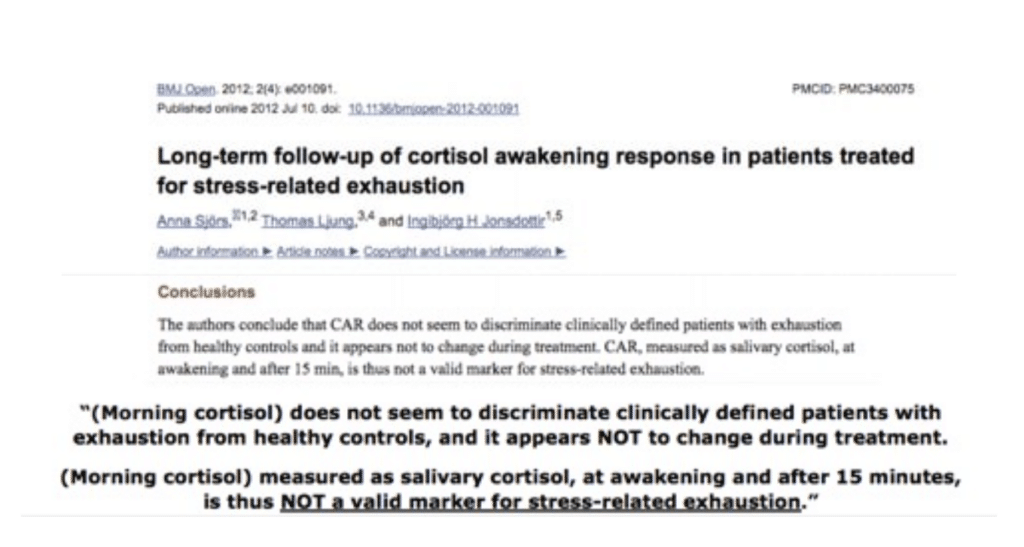

But here are several screenshots of some of the actual studies (along with my summary and quotes of findings) of just a few of the studies so you can see for yourself:

Since most people with Burnout Syndrome and Stress-Related Exhaustion do not have any detectable abnormality in cortisol levels, it is clear that low cortisol levels are clearly not the cause of the symptoms of Burnout Syndrome or Stress-Related Exhaustion Disorder (i.e. the symptoms claimed to be caused by “adrenal fatigue.”)

Again, the science simply does NOT support the “adrenal fatigue” theory.

As one review of the scientific research (the highest level of evidence) titled “Hypocortisolism: An Evidence-Based Review” put it:

“Although adrenal fatigue or burn out of the adrenal gland subsequent to chronic stress has been proposed as one mechanism by which hypocortisolism [low cortisol] develops, current medical research does not support this claim.”[22]

In fact, the Endocrine Society, representing 14,000 endocrinologists (MDs who specialize in hormonal health), has publicly stated:

“‘Adrenal fatigue’ is not a real medical condition. There are no scientific facts to support the theory that long-term mental, emotional, or physical stress drains the adrenal glands and causes many common symptoms.”[23]

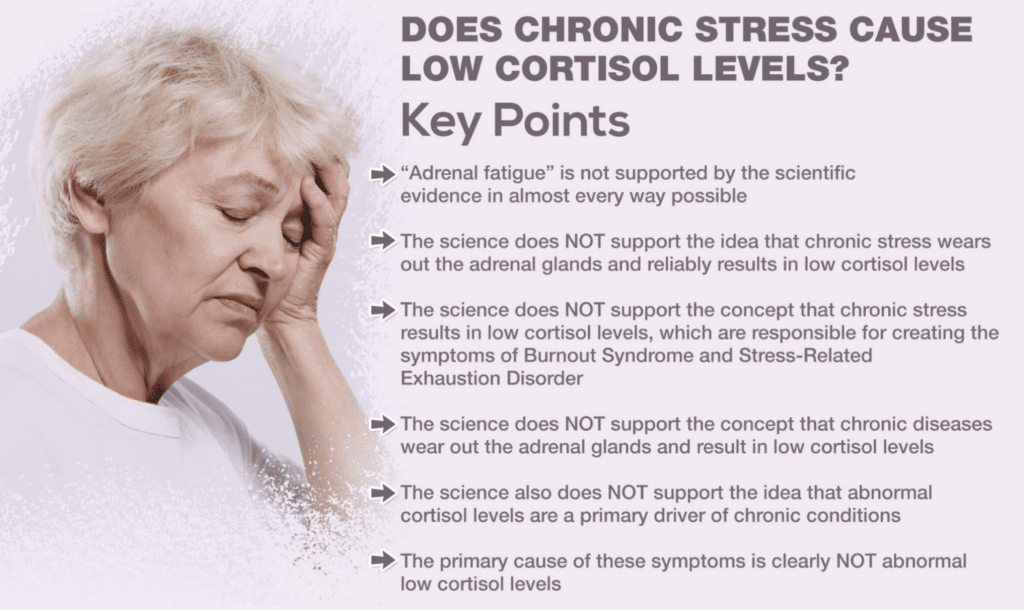

KEY POINTS

- “Adrenal fatigue” is not supported by scientific evidence in almost every way possible. I.e. Every place we can look to find scientific support for the theory of adrenal fatigue fails to support the theory.

- The science does not support the idea that there is any sort of reliable pattern where chronic stress wears out the adrenal glands and results in low cortisol levels. Virtually all of the existing evidence clearly contradicts this theory.

- The science also does NOT support the concept that even overt chronic diseases (which are a form of chronic metabolic stress/allostatic load) wear out the adrenal glands and result in low cortisol levels.

- The science also does not support the theory that Burnout Syndrome or Stress-Related Exhaustion have any connection whatsoever to abnormal adrenal function or to low cortisol levels.

- The vast majority of people with stress-related fatigue, Stress-Related Exhaustion Disorder or Burnout Syndrome have either perfectly normal or slightly higher cortisol levels.

- Given that most people with these symptoms don’t have low cortisol levels (or abnormal adrenal function), then we know definitively that low cortisol levels cannot possibly be causing these symptoms.

- Moreover, since most people with Burnout Syndrome and Stress-Related Exhaustion Disorder (i.e. people inclined to be diagnosed or self-diagnose themselves with “adrenal fatigue”) actually have normal (and sometimes even high) cortisol levels, it is negligent and/or counterproductive to further boost cortisol levels, based on the assumption that the person has low cortisol levels.

- It is not supportable by the evidence to claim that abnormal cortisol levels are causing stress-related exhaustion/fatigue/burnout or that fixing cortisol levels is the best solution for these symptoms.

- Put another way: It is nonsense to claim that that low cortisol levels (“adrenal burnout”) are the “cause” of these conditions/symptoms.

- Given the scientific evidence on this subject, it makes no sense to continue to try to explain the cause of fatigue/exhaustion/burnout through the lens of the adrenals and cortisol levels. The primary cause of these symptoms is clearly NOT abnormal cortisol levels, so we must stop trying to fix these symptoms as though the adrenals/cortisol levels are the primary cause.

In summary, all of the basic tenets of the “adrenal fatigue” theory are not supported by the evidence.

CLICK HERE TO READ PART 2 – THE REAL FACTORS THAT CAUSE LOW CORTISOL LEVELS

(In Part 2, we’ll cover the real factors responsible for causing low morning cortisol levels. Specifically, now that we know that chronic stress does not wear out our adrenals and lead to “adrenal fatigue,” we’ll examine the real factors that cause some people to have abnormal cortisol levels.)

References

[1] Wüst S., et.al., (2000) Genetic factors, perceived chronic stress, and the free cortisol response to awakening, Psychoneuroendocrinology doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(00)00021-4

[2] Wüst S., et.al., (2000) Genetic factors, perceived chronic stress, and the free cortisol response to awakening, Psychoneuroendocrinology doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(00)00021-4

[3] Wüst S., et.al., (2000) Genetic factors, perceived chronic stress, and the free cortisol response to awakening, Psychoneuroendocrinology doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(00)00021-4

[4] Ockenfels ´, MC., et al., (1995), Effect of Chronic Stress Associated With Unemployment on Salivary Cortisol: Overall Cortisol Levels, Diurnal Rhythm, and Acute Stress Reactivity, Journal Of Behavioral Medicine, Psychosomatic Medicine: September/October 1995 – Volume 57 – Issue 5 – p 460-467

[5]Schultz, P. PhD., et al., (1998) Increased free cortisol secretion after awakening in chronically stressed individuals due to work overload, Stress & Health, doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1700(199804)14:2<91::AID-SMI765>3.0.CO;2-S

[6] Liao, J., (2013) Is There an Association between Work Stress and Diurnal Cortisol Patterns? Findings from the Whitehall II Study

[7] Ladreling, M., et al., The demand control model and circadian saliva cortisol variations in a Swedish population based sample (The PART study)

[6] Badrick, E., et. al., (2007) The Relationship between Smoking Status and Cortisol Secretion, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 92, Issue 3, 1 March 2007, Pages 819–824

[7] Cadegiani, FA., et. al., (2017) Hormonal aspects of overtraining syndrome: a systematic review, BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2017; 9: 14. Published online 2017 Aug 2. doi: 10.1186/s13102-017-0079-8

[8] Cadegiani, FA., et. al., (2017) Hormonal aspects of overtraining syndrome: a systematic review, BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2017; 9: 14. Published online 2017 Aug 2. doi: 10.1186/s13102-017-0079-8

[9] Van Uum, SHM., et. al., Elevated content of cortisol in hair of patients with severe chronic pain: A novel biomarker for stress, The International Journal on the Biology of Stress, Volume 11, 2008 – Issue 6

[10] Van Uum, SHM., et. al., Elevated content of cortisol in hair of patients with severe chronic pain: A novel biomarker for stress, The International Journal on the Biology of Stress, Volume 11, 2008 – Issue 6

[11] Riva R., et. al., (2012) Comparison of the cortisol awakening response in women with shoulder and neck pain and women with fibromyalgia, Psychoneuroendocrinology, Volume 37, Issue 4, April 2012, Pages 587

[12] Brunner, EJ. Et. al., (2002) Adrenocortical, autonomic, and inflammatory causes of the metabolic syndrome: nested case-control study. Circulation. 2002 Nov 19;106(21):2659-65.

[14] Chida, Y., et al., (2009) Cortisol awakening response and psychosocial factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis

[13] Balckburn-Munro, RE., et. al., (2001) Chronic Pain, Chronic Stress and Depression: Coincidence or Consequence?, Journal of Neuroendocrinology 21 December 2001 //doi.org/10.1046/j.0007-1331.2001.00727.x

[14] Manenschijn, L., et. al. (2013), High Long-Term Cortisol Levels, Measured in Scalp Hair, Are Associated With a History of Cardiovascular Disease, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 98, Issue 5, 1 May 2013, Pages 2078–2083

[15] Walker, EF., et. al., (2013) Cortisol Levels and Risk for Psychosis: Initial Findings from the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study. Biol Psychiatry. 2013 Sep 15; 74(6): 410–417.

[16] Girshkin L., et. al., (2014) Morning cortisol levels in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014 Nov;49:187-206. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.07.013. Epub 2014 Jul 21.

[17] Bradley, AJ., et. al., (2010) A systematic review of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis function in schizophrenia: implications for mortality, J Psychopharmacol. 2010 Nov; 24(4_supplement): 91–118. doi: 10.1177/1359786810385491

[i]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18378875

[18] Girshkin L., et. al., (2014) Morning cortisol levels in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014 Nov;49:187-206. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.07.013. Epub 2014 Jul 21.

[19] Agha-Hosseini F., et. al., (2016), The association of elevated plasma cortisol and Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis, a neglected part of immune response. Acta Clin Belg. 2016 Apr;71(2):81-5. doi: 10.1080/17843286.2015.1116152. Epub 2016 Feb 6.

[20] Fries E., et. al., (2009), The cortisol awakening response (CAR): facts and future directions. Int J Psychophysiol. 2009 Apr;72(1):67-73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.03.014. Epub 2008 Sep 30.

[21] Swaab DF, et. al., (1994) Increased cortisol levels in aging and Alzheimer’s disease in postmortem cerebrospinal fluid. J Neuroendocrinol. 1994 Dec;6(6):681-7.

[22] Edwards. LD., et. al., (2011) Hypocortisolism: An Evidence-based Review, Integrative Medicine ‘

[23] Newman, T. (2018) Is adrenal fatigue a real condition? Medical News Today

[24] Shahili Jain, (2016) Cortisol, the Intergenerational Transmission of Stress, and PTSD: An Interview With Dr. Rachel Yehuda

[25] Christianson A. MD., Kresser C., (2016) Adrenal Summit Interview

[26] Blockmans, D., et al. (2003) Combination therapy with hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone does not improve symptoms in chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study, The Americal Journal of Medicine, June 15, 2003Volume 114, Issue 9, Pages 736–741

[27] Cleare AJ. (2003) The Neuroendocrinology of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

[28] Badrick et al. (2008). The Relationship between Alcohol Consumption and Cortisol Secretion in an Aging Cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Mar; 93(3): 750–757.