Table of Contents

To find out whether you have or do not have a medical condition, most people turn to medical tests. A medical examination is any medical procedure (such as a blood test, saliva test, muscle biopsy or ultrasound scan) that is performed to detect, diagnose, or monitor diseases/dysfunctions. 1 Some tests (such as genetic tests) are also used to determine the susceptibility of an individual to disease. Medical tests relate to anatomical and clinical pathology and are typically performed in a medical laboratory or hospital by a healthcare professional.

When it comes to adrenal fatigue, however, traditional medical tests often show no detectable abnormality. This does not mean that the symptoms such as low energy and brain fog are not real. The symptoms associated with adrenal fatigue typically include chronic fatigue (that is not relieved by sleep), an inability to manage stress, anxiety, depression, body aches, sleep disturbances, dry skin, weight fluctuations, circulatory issues, and digestive problems. 2 As these symptoms are non-specific and can be generally associated with a whole host of diseases/disorders, diagnosing adrenal fatigue can be tricky.

In 1998, Dr. James Wilson coined the term “adrenal fatigue” to identify below-optimal adrenal function (mostly resulting from stress) and distinguish it from Addison’s Disease (which is a long-term endocrine disorder in which the adrenal glands do not produce enough steroid hormones). 3 Though the term often appears in popular health books and on alternative medicine websites, it isn’t an accepted medical diagnosis by medical professionals. 4

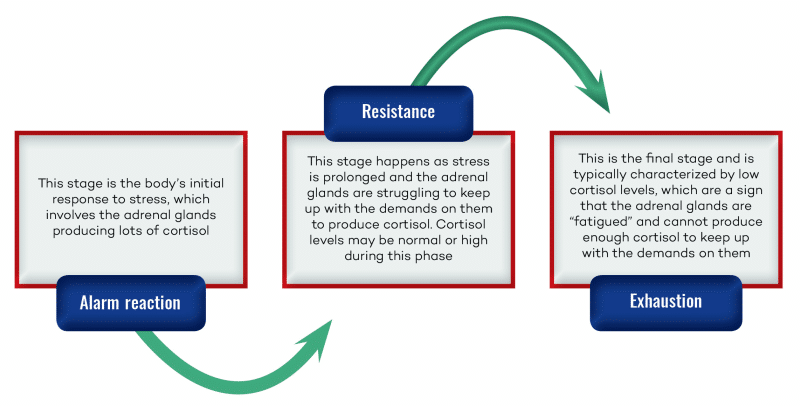

The theory behind Adrenal Fatigue is primarily based on the work of researcher Hans Selye on General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS). 5 He proposed that the body goes through 3 phases when exposed to chronic stress, ultimately leading to shut down or system-wide failure. The three stages are generally described as follows:

- Alarm reaction – the body’s initial response to stress, which involves the adrenal glands producing lots of cortisol.

- Resistance – when stress is prolonged, the adrenal glands struggle to keep up with cortisol production, and cortisol levels may be normal or high.

- Exhaustion – at this stage, the adrenals are “fatigued” and can no longer produce enough cortisol to keep up with demands and cortisol levels dip.

Can you be tested for adrenal fatigue

Functional medicine practitioners use a variety of methods to test for adrenal fatigue. Usually, the tests listed below are ordered when adrenal fatigue is suspected:

Cortisol test

This is the primary test used to diagnose adrenal fatigue. Your doctor may order a saliva, blood, or urine test to measure your cortisol, but salivary cortisol tests tend to be the most accurate. As cortisol levels vary dramatically, starting high when we wake up and then tapering off until they reach their lowest point late at night, a single test is insufficient. Usually, at least four individual measurements are needed at various times of the day to map your 24-hour cortisol pattern.

ACTH challenge

This is when a dose of ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone) is injected, and cortisol levels are measured before and after. A healthy spike after the injection, showing at least a doubling of standards, is a sign of healthy adrenal function.

Thyroid tests

As the hypothalamus and pituitary gland are interconnected and interdependent weakness in one area can cause changes in the other. There are several blood markers of thyroid function including TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone) produced by the pituitary gland on the instruction of the hypothalamus. It stimulates the thyroid gland to produce T3 and T4. Levels of TSH in the blood are inversely proportional to thyroid function.

In adrenal fatigue sufferers, it is theorized that the thyroid is not functioning correctly, so TSH readings are expected to be high (>2.0)

T3, which is produced when TSH stimulates the thyroid. Optimal values should be between 100-200 pg/ml range. 6

T4 is the storage form of the hormone. If it is too low, it can suggest an underactive thyroid. The test usually measures free or “unbound” T4, which is available for immediate use.

DHEA-sulfate serum test

This is another test often performed by alternative medicine practitioners, which tests the level of the hormone dehydroepiandrosterone. It is believed that levels of DHEA fall concomitantly with cortisol as stress levels increase. This is because stress hormone production ‘steals’ resources from sex hormone production. 7

Some of these medical tests are available for home testing. This includes cortisol and glucocorticoid stimulation or suppression tests, as well as thyroid, ACTH, and DHEA tests.

In addition to the above tests, a diagnosis often involves feedback from the patient, which may or may not include questionnaires. 8

Does Adrenal Fatigue exist?

Well, that depends on who you ask. If you ask an alternative medical practitioner, they will likely be convinced that 70% or 80% of people they see have “adrenal fatigue,” and that it is unquestionably real. On the other hand, most conventional MDs will think you are unscientific if you believe in the pseudoscience of “adrenal fatigue.”

To put it simply, the symptoms of adrenal fatigue are REAL, and there is a growing epidemic of people experiencing this specific set of symptoms. There is almost no scientific evidence to claim that the cause is related to the adrenal glands.

In fact, a recent systematic review of 58 studies showed that there is no scientific evidence to substantiate that adrenal impairment is a cause of fatigue. 9 Even when cortisol levels were checked four times in 24 hours, there was no difference between fatigued and healthy patients in 61.5% of the studies. Also, there were no detectable differences in the amount or severity of symptoms (such as fatigue) between people with extremely high cortisol levels vs. deficient cortisol levels vs. normal cortisol levels!

This means that there must be a deeper underlying cause of the extreme tiredness related to “adrenal fatigue,” which has led many to a more complex and sophisticated theory that involves the HPA axis.

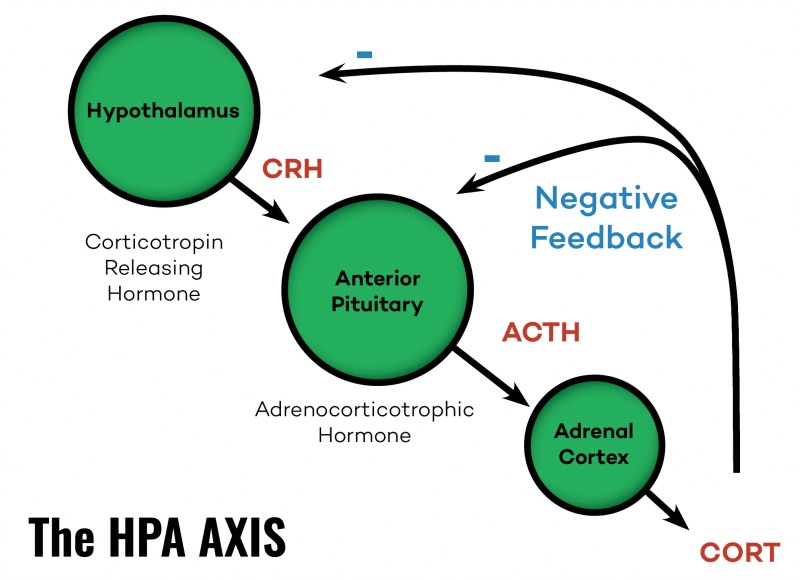

The HPA axis includes three interconnected and interdependent parts of the body; the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the adrenal glands. The hypothalamus produces corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) in response to stress, which then stimulates your pituitary gland to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). The more stressed your body is, the more CRH your hypothalamus will produce. ACTH acts on the adrenal glands to increase the production of glucocorticoids. These are hormones that are involved in regulating metabolic rate, inflammation, and immune response. The most well-known of these is cortisol.

Cortisol, in turn, prepares your body to withstand stressful triggers by stimulating the production of catecholamines and triggering fight-or-flight physiology in the body. Normally, a feedback loop calms the system back down and prevents the overproduction of stress hormones. Certain factors can cause the HPA axis to become chronically over-activated and, ultimately, to dysfunction. This can indeed cause abnormal cortisol levels and contribute to several symptoms, like fatigue and sleep issues, and others associated with “adrenal fatigue.” Though there is no science on adrenal fatigue, there is plenty of science on HPA axis dysfunction. 10111213

What this model shows us is that the body is more complex than the theory of adrenal fatigue supposes. Also, when cortisol levels are low, it’s almost always because the body wants them to be that way! Thus, trying to “heal the adrenals” and raise cortisol levels is often profoundly misguided.

What is adrenal insufficiency?

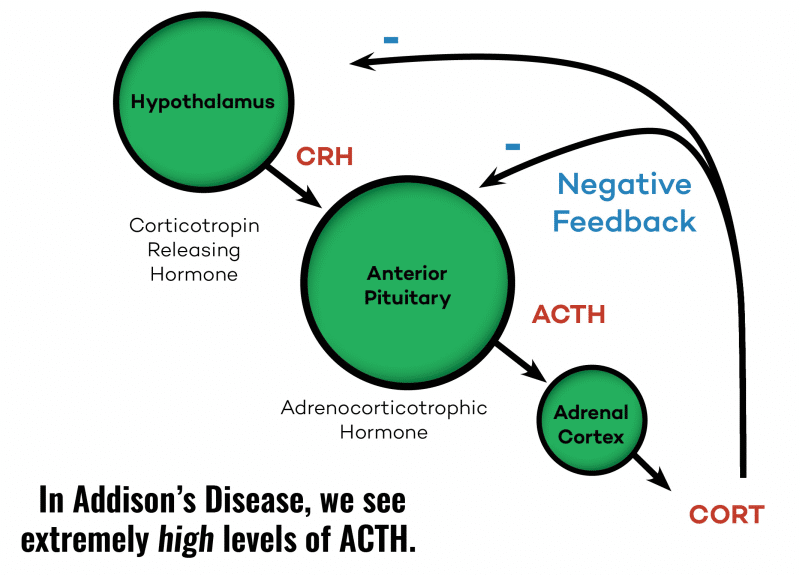

Adrenal insufficiency is also known as Addison’s disease. It is a real adrenal condition, distinct from “adrenal fatigue,” that is characterized by high levels of CRH and ACTH being produced by the hypothalamus. CRH and ACTH usually stimulate the adrenals to produce glucocorticoids (including cortisol).

However, in Adrenal insufficiency, this does not happen. In other words, the adrenal glands just cannot produce enough stress hormones, possibly due to the destruction of the adrenal cortex. 14 Symptoms of Addison’s disease include fatigue, body aches, low blood pressure, lightheadedness, abnormal blood levels of sodium and potassium, unexplained weight loss, skin discoloration, loss of body hair, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. 15

If not Adrenal Fatigue, then what?

Although HPA axis dysfunction is a better theory that adrenal dysfunction, recent prospective cohort studies suggest that there are no HPA axis changes present during the early stages of the propagation of fatigue, thereby confirming that it cannot be the cause. The same study also suggests “a reversed direction of causation (ie, that the illness leads to HPA axis change rather than the other way around), which is further supported by the findings that modifying cognitive-behavioral components of the illness leads to normalization of the HPA axis.” 16

If it is not HPA dysfunction, one explanation could be that a huge proportion of people who have these symptoms simply have what is termed chronic fatigue syndrome, which is medically recognized and presents with exactly the same symptoms as “adrenal fatigue.”

In fact, “burnout syndrome,” “adrenal fatigue,” and “Chronic Fatigue Syndrome” may all exist on a spectrum of energy and fatigue, and it is just a matter of the intensity/severity of symptoms. Instead of using confusing labels, it might be prudent just to call it fatigue.

Dysfunctions in any system of the body can cause fatigue but are usually due to environmental and lifestyle factors, including:

- Staying up late at night (i.e. being a night owl) 171819

- Lack of morning light exposure 202122

- Night eating 23

- Being overweight 24

- Nutrient deficiencies (including deficiencies of vitamin C, folic acid, pantothenic acid, biotin, calcium, potassium, zinc, and iron), which can all be corrected with multivitamin supplements 25

- Rumination and neuroticism (which contribute to depression) 26

- Helplessness, hopelessness and low self-esteem 2728

- Cynicism 29

- Taking certain medications, such as anti-depressants 30, aspirin 31, Tylenol (acetaminophen) 32, opioids 33 and some blood pressure-lowering drugs 34

- The recent loss of a partner and/or social isolation 35,

- Ethnicity – African Americans and Hispanics tend to have lower morning cortisol levels than Caucasians 36,

- Low physical activity levels 37,

- The anticipation of a low-stress day/vacation 38

- Lower socioeconomic status 39,

- Psychological trauma or PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) 40,

- Genetics – different groups of people have different baseline cortisol levels that can be inherited 4142

- Toxins – such as glyphosate, fungicides, BPA found in plastics, and heavy metals have been shown to interfere with blood cortisol levels 434445

- Inflammation – resulting from oxidative stress can cause the body to suppress Cortisol levels 46 intentionally

- Poor sleep 4748 – resulting from insufficient sleep duration and/or quality, which may be due to conditions such as sleep apnea or simply from poor circadian rhythm and sleep hygiene habits

In order to find the right treatment, however, it is important to understand the primary system that causes fatigue. The mitochondria are the main powerhouse or energy generators of the cell, so it may come as no surprise that ultimately it is mitochondrial dysfunction that causes fatigue. Fatigue is fundamentally an imbalance between energy supply and energy demand.

A chronic deficit of energy caused by increased demands on the body as a result of stress is the root of fatigue. The fatigue that results serves a purpose, to give your body the rest it needs to recover from the stress. When fatigue sets in, there is a problem with either energy production or energy demand. For the vast majority of people, energy production is a big obstacle, and that is why improving mitochondrial function is critical.

There is plenty of scientific evidence to back this up. 495051 In fact, the more chronic and unrelenting fatigue you have, the more that dysfunctional mitochondria are probably the cause.

Basically, when mitochondria are not working well, and you use up any/all available energy, the mitochondria get depleted. If the demand for energy does not decrease or cease, metabolites accumulate in the cell, which compounds the problem and result in severe fatigue or “burnout.” Dr. Robert Naviaux, a prominent researcher and expert in the field, has found that energy generation is not the only role of mitochondria, but that they are also responsible for cell defense. 52 This has huge implications for understanding fatigue. When mitochondria sense danger and go into defense mode, energy production takes a back seat and becomes compromised. If the situation is not resolved and cell defense mode persists abnormally, whole-body metabolism and the gut microbiome are disturbed, the collective performance of multiple organ systems is impaired, the behavior is changed, and chronic disease results. 53

Takeaway:

Now that you understand the real cause of fatigue, it is clear that treatment should include measures to improve mitochondrial function. Supplementing with cortisol or adrenal hormones, which is often suggested as a treatment for severe “adrenal fatigue,” is misguided.

Cortisol replacement can be dangerous even in small doses, so be extremely cautious. Unintended consequences can include osteoporosis, diabetes, weight gain, and heart disease. 54 It can be extremely frustrating when you have real symptoms and suffer from debilitating fatigue, to be told that there is nothing wrong with you.

Before buying expensive protocols over the internet to treat something that does not exist, reexamine your lifestyle and focus on eating a healthy diet, low in sugar and processed foods, getting good quality sleep, limiting environmental toxins, and exercising regularly. For more information on how to improve mitochondrial function read the article titled “How to Live to 100 with Mitochondrial Biogenesis.”

References[+]

| ↑1 | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medical_test |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑7 | https://www.healthline.com/health/adrenal-fatigue-test |

| ↑3 | https://adrenalfatigue.org/what-is-adrenal-fatigue/ |

| ↑4, ↑9 | Cadegiani, Flavio A, and Claudio E Kater. “Adrenal fatigue does not exist: a systematic review.” BMC endocrine disorders vol. 16,1 48. 24 Aug. 2016, doi:10.1186/s12902-016-0128-4 |

| ↑5 | Jackson M. “Evaluating the Role of Hans Selye in the Modern History of Stress.” Stress, Shock, and Adaptation in the Twentieth Century. Rochester (NY): University of Rochester Press; 2014 Feb. Chapter 1. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK349158/) |

| ↑6 | https://www.healthline.com/health/t3 |

| ↑8 | https://adrenalfatiguesolution.com/testing-for-adrenal-fatigue/ |

| ↑10 | Ben-Zvi, Amos et al. “Model-based therapeutic correction of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction.” PLoS computational biology vol. 5,1 (2009): e1000273. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000273 |

| ↑11 | Stephens, Mary Ann C, and Gary Wand. “Stress and the HPA axis: role of glucocorticoids in alcohol dependence.” Alcohol research : current reviews vol. 34,4 (2012): 468-83. |

| ↑12 | Guilliams, Thomas G. Ph.D. and Edwards, Lena M.D. “Chronic Stress and the HPA Axis: Clinical Assessment and Therapeutic Considerations.” The Standard, Point Institute of Nutraceutical Research, vol 9,2 (2010) |

| ↑13 | Mark A. Demitrack & Leslie J. Crofford (1995) Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Dysregulation in Fibromylagia and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome:, Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain, 3:2, 67-73, DOI: 10.1300/J094v03n02_09 |

| ↑14 | Pazderska, A. And Pearce, S.H. “Adrenal insufficiency – recognition and management.” Clin Med (Lond). 2017 Jun;17(3):258-262. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.17-3-258. |

| ↑15 | Charmandari, E., et al. “Adrenal insufficiency.” The Lancet, Volume 383, Issue 9935, 21–27 June 2014, Pages 2152-2167, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61684-0 |

| ↑16 | Cleare AJ. (2003) “The HPA Axis and the genesis of Chronic Fatigue.” Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 15(2):55-9 · April 2004, doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2003.12.002 |

| ↑17 | Abbruzzese EA., et al. (2014) “The Influence Of The Chronotype On The Awakening Response Of Cortisol In The Morning.” Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, Vol 1 No 7 (2014), doi:10.14738/assrj.17.519 |

| ↑18 | Oginska H., et al. (2010) “Chronotype, sleep loss, and diurnal pattern of salivary cortisol in a simulated daylong driving.” Chronobiology International 27(5):959-74 · July 2010, doi:10.3109/07420528.2010.489412 |

| ↑19 | BM Kudielka et al. (2005) “Morningness and Eveningness: The Free Cortisol Rise After Awakening in “Early Birds” and “Night Owls”.” Biol Psychol. 2006 May;72(2):141-6. Epub 2005 Oct 19, doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.08.003 |

| ↑20 | Thorn, L., et al. (2011) “Seasonal differences in the diurnal pattern of cortisol secretion in healthy participants and those with self-assessed seasonal affective disorder.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, Volume 36, Issue 6, July 2011, Pages 816-823, doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.11.003 |

| ↑21 | Gabel, V., et. al., (2013) “Effects of Artificial Dawn and Morning Blue Light on Daytime Cognitive Performance, Well-being, Cortisol and Melatonin Levels.” The Journal of Biological and Medical Rhythm Research, Volume 30, 2013 – Issue 8, doi:10.3109/07420528.2013.793196 |

| ↑22 | Mariana G. Figueiro and Mark S. Rea, “Short-Wavelength Light Enhances Cortisol Awakening Response in Sleep-Restricted Adolescents,” International Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 2012, Article ID 301935, 7 pages, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/301935. |

| ↑23 | Goel, N., et. al. (2009) “Circadian Rhythm Profiles in Women with Night Eating Syndrome.” J Biol Rhythms. 2009 Feb; 24(1): 85–94. doi: 10.1177/0748730408328914 |

| ↑24 | Champaneri, Shivam et al. “Diurnal salivary cortisol is associated with body mass index and waist circumference: the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.” Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.) vol. 21,1 (2013): E56-63. doi:10.1002/oby.20047 |

| ↑25 | Camfield, DA., et. al., (2013) “The Effects of Multivitamin Supplementation on Diurnal Cortisol Secretion and Perceived Stress, Nutrients.” 2013 Nov; 5(11): 4429–4450. Published online 2013 Nov 11. doi: 10.3390/nu5114429 |

| ↑26 | Hsiao, FH., et. al., (2010) “The self-perceived symptom distress and health-related conditions associated with morning to evening diurnal cortisol patterns in outpatients with major depressive disorder.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, Volume 35, Issue 4, May 2010, Pages 503-515, doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.08.019. Epub 2009 Sep 22 |

| ↑27 | Hauner, KKY., et. al., “Neuroticism and Introversion are Associated with Salivary Cortisol Patterns in Adolescents, Psychoneuroendocrinology.” 2008 Nov; 33(10): 1344–1356. Published online 2008 Sep 21. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.07.011 |

| ↑28 | Zilioli, S., et. al., (2016) “Childhood Adversity, Self-Esteem, and Diurnal Cortisol Profiles across the Lifespan.” Psychol Sci. 2016 Sep; 27(9): 1249–1265. Published online 2016 Aug 1. doi: 10.1177/0956797616658287 |

| ↑29 | Sjogren, E., et. al., (2006) “Diurnal saliva cortisol levels and relations to psychosocial factors in a population sample of middle-aged swedish men and women.” International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, September 2006, Volume 13, Issue 3, pp 193–200, doi:10.1207/s15327558ijbm1303_2 |

| ↑30 | Sjörs, Anna et al. “Long-term follow-up of cortisol awakening response in patients treated for stress-related exhaustion.” BMJ open vol. 2,4 e001091. 10 Jul. 2012, doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001091 |

| ↑31 | Nye, EJ., et al., (1997) “Aspirin Inhibits Vasopressin-Induced Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Activity in Normal Humans.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 82, Issue 3, 1 March 1997, Pages 812–817, doi:10.1210/jcem.82.3.3820 |

| ↑32 | Oskarsson A, et al., “Acetaminophen Increases Aldosterone Secretion While Suppressing Cortisol and Androgens: A Possible Link to Increased Risk of Hypertension.” Am J Hypertens. 2016 Oct;29(10):1158-64. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpw055. Epub 2016 May 23. |

| ↑33 | Lee, Angela S, and Stephen M Twigg. “Opioid-induced secondary adrenal insufficiency presenting as hypercalcaemia.” Endocrinology, diabetes & metabolism case reports vol. 2015 (2015): 150035. doi:10.1530/EDM-15-0035 |

| ↑34 | Lewis, M J et al. “The effects of propranolol and acebutolol on the overnight plasma levels of anterior pituitary and related hormones.” British journal of clinical pharmacology vol. 12,5 (1981): 737-42. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1981.tb01298.x |

| ↑35 | Doane, LD., et. al., (2009) “Loneliness and Cortisol: Momentary, Day-to-day, and Trait Associations,” Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010 Apr; 35(3): 430–441. Published online 2009 Sep 9. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.08.005 |

| ↑36, ↑39 | Hajat, A., et. al., (2010) “Socioeconomic and race/ethnic differences in daily salivary cortisol profiles: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.” Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010 Jul; 35(6): 932–943. Published online 2010 Jan 29. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.12.009 |

| ↑37 | Tryon WW, et al. (2004) “Chronic fatigue syndrome impairs circadian rhythm of activity level.” Physiol Behav. 2004 Oct 15;82(5):849-53, doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.07.005 |

| ↑38 | Fries E., et al. (2008) “The cortisol awakening response (CAR): Facts and future directions.” Int J Psychophysiol. 2009 Apr;72(1):67-73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.03.014. Epub 2008 Sep 30 |

| ↑40 | Shahili Jain, (2016) “Cortisol, the Intergenerational Transmission of Stress, and PTSD: An Interview With Dr. Rachel Yehuda.” PLOS, doi:0000-0002-8715-2896 |

| ↑41 | Genetics Home Reference, Familial glucocorticoid deficiency |

| ↑42 | Genetics Home Reference, 21-hydroxylase deficiency |

| ↑43 | Sanderson, T.J. (2006) “The steroid hormone Biosynthesis pathway as a target for endocrine-disrupting chemicals.” Toxicological Sciences, 94(1), pp. 21–3. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl051. |

| ↑44 | Panagiotidou, E., Zerva, S., Mitsiou, D.J., Alexis, M.N., Kitraki, E. and ekitraki (2014) “Perinatal exposure to low-dose bisphenol A affects the neuroendocrine stress response in rats.” Journal of Endocrinology, 220(3), pp. 207–218. doi: 10.1530/JOE-13-0416. |

| ↑45 | Dyer C.A. (2007) Heavy Metals as Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. In: Gore A.C. (eds) Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Contemporary Endocrinology. Humana Press, doi:10.1007/1-59745-107-X_5 |

| ↑46 | Morris, G., et. al., (2017) “Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Hypofunction in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) as a Consequence of Activated Immune-Inflammatory and Oxidative and Nitrosative Pathways.” Mol Neurobiol. 2017, Nov;54(9):6806-6819, doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0170-2. Epub 2016 Oct 20. |

| ↑47 | Bozic, L., et. al., (2016) “Morning cortisol levels and glucose metabolism parameters in moderate and severe obstructive sleep apnea patients.” Endocrine. 2016 Sep;53(3):730-9. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-0925-6. Epub 2016 Mar 21. |

| ↑48 | Tell, Dina et al. “Day-to-day dynamics of associations between sleep, napping, fatigue, and the cortisol diurnal rhythm in women diagnosed as having breast cancer.” Psychosomatic medicine vol. 76,7 (2014): 519-28. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000097 |

| ↑49 | Torrell, H., et al. “Mitochondrial dysfunction in a family with psychosis and chronic fatigue syndrome.” Mitochondrion. 2017 May;34:1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2016.10.007. Epub 2016 Oct 28. |

| ↑50 | Filler, K., et al. “Association of Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Fatigue: A Review of the Literature.” BBA Clin. 2014 Jun 1;1:12-23, doi:10.1016/j.bbacli.2014.04.001 |

| ↑51 | Gerwyn, M., et al. “Mechanisms Explaining Muscle Fatigue and Muscle Pain in Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): a Review of Recent Findings.” Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017 Jan;19(1):1. doi: 10.1007/s11926-017-0628-x. |

| ↑52, ↑53 | Naviaux, R.K. “Metabolic features of the cell danger response.” Mitochondrion. 2014 May;16:7-17. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2013.08.006. Epub 2013 Aug 24. |

| ↑54 | https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-supplements-adrenal-hormones/adrenal-support-supplements-may-contain-unsafe-ingredients-idUSKBN1HW2VV |