As we covered in Part 1 on debunking adrenal fatigue, it is clear that:

- Chronic stress does not “fatigue” our adrenals and cause low cortisol levels.

- Chronic disease (or really any measurement of poor health status or total body stress load) also does not “fatigue” our adrenals and cause low cortisol levels.

- “Adrenal fatigue”/low cortisol levels are NOT the cause of the symptoms of stress-related fatigue/burnout/exhaustion.

In this article and video/podcast, we’re going to cover the exact specific factors known to cause (or be reliably associated with) low morning cortisol levels.

Table of Contents

Download or Listen on iTunes

Listen outside iTunes

If Not “Adrenal Fatigue”, Then What’s Really Going On In People Who Have Low Morning Cortisol Levels?

First, let’s get clear on what type of cortisol findings we’re actually talking about that get people diagnosed with “adrenal fatigue.”

We’re NOT talking about severely low 24-hour output of cortisol levels, which is likely indicative of Addison’s Disease. That is extremely rare and has basically nothing to do with “adrenal fatigue” or stress-related exhaustion/burnout.

The vast majority of people who are told they have “low cortisol” or “adrenal fatigue” have not actually been determined to have low total 24-hour output of cortisol.

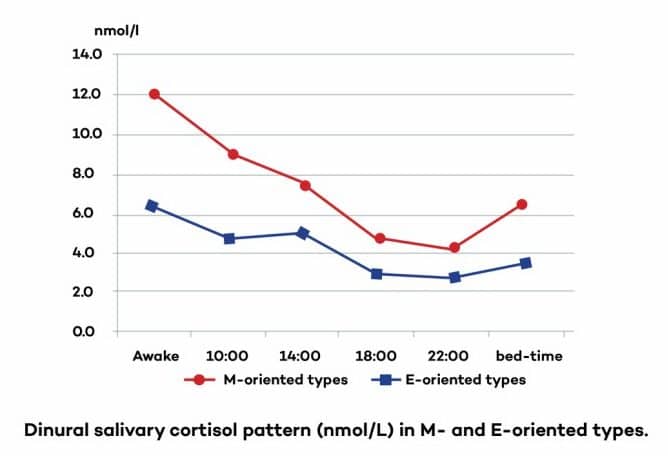

What the vast majority of these people – more than 90% (conservatively) — have is SLIGHTLY lower morning cortisol levels and sometimes also SLIGHTLY higher evening cortisol levels. This is also called a “flattened diurnal cortisol curve.”

This means that a person will typically have slightly lower morning cortisol levels (when cortisol should be higher) and sometimes also slightly higher cortisol levels in the evening (when cortisol should be lower) – as compared with people with an ideal cortisol rhythm.

As I showed you in Part 1 (Debunking adrenal fatigue), while this pattern often gets people diagnosed with “adrenal fatigue”, the reality is that the science does not support the notion that this cortisol pattern is caused by “adrenal burnout” or any sort of actual inability of the adrenal glands to produce enough cortisol (as the “adrenal fatigue” theory proposes).

Indeed, unpublished research from a lab that does cortisol testing called Precision Analytical found that in 2,000 people with low morning salivary cortisol levels, when total cortisol production is measured via the urine, 85% of those people actually had normal or even high total cortisol production! [i]

Put another way:

- Only 15% of people being told they have “low cortisol levels” (and likely being diagnosed with “adrenal fatigue”) actually have low cortisol production!

- The vast majority of people with low morning cortisol levels do not have any deficit in the ability of their adrenals to produce cortisol. They have perfectly normal total cortisol output.

- And many people being diagnosed with “adrenal fatigue” and told that their adrenals aren’t producing enough cortisol are in reality, producing abnormally HIGH amounts of cortisol over 24 hours.

So even where someone has low morning cortisol levels and this “flat diurnal curve” of cortisol, that should not be interpreted as or “adrenal fatigue” or “adrenal burnout.” This finding is almost always not the result of any actual problem with the adrenals or inability to produce enough cortisol.

In other words, there is a difference between a timing shift of cortisol output vs. the actual amount of cortisol being produced over 24 hours.

It’s typically not that the adrenals aren’t producing enough cortisol – it’s that the timing of cortisol release is being thrown off. (We’ll go over why this happens in the next section.)

Again, it is perfectly possible (and actually very common) to have low morning cortisol levels but normal or even HIGH total 24-hour output of cortisol.

Remember, the most common thing going on is not actually “low cortisol levels.” The most common abnormal cortisol finding is a flattened diurnal curve of cortisol – which simply means slightly lower morning cortisol levels and sometimes also slightly higher evening cortisol levels.

So what’s going on in the body that leads to low morning cortisol levels?

The 5 Primary Mechanisms of Low Morning Cortisol Levels

At this point, we now know the following 3 key points that completely disprove the adrenal fatigue theory:

- Chronic stress does NOT generally lead to low cortisol levels.

- Low cortisol levels are generally NOT associated with Burnout Syndrome or Stress-Related Exhaustion Disorder.

- The vast majority of people with low morning cortisol levels typically do NOT actually have any problem with their adrenals being able to produce enough cortisol.

Now, even though we know that low cortisol levels (i.e. “adrenal fatigue”) is NOT actually the real cause of the symptoms associated with Burnout Syndrome and Stress-Related Exhaustion, some people are still skeptical and still want to believe in the adrenal fatigue theory, and say “well then why did my test show that I do have low morning cortisol levels?”

Indeed, the question now becomes…

If it’s not chronic stress wearing out your adrenals, then what are the real factors responsible for low morning cortisol levels?

We’re going to answer that definitively in this section and the following section, but first, there is something very important I need to remind you of…

Since cortisol levels/adrenal function are NOT the cause of burnout/exhaustion/chronic fatigue symptoms, trying to fix the symptoms fixing your adrenals/cortisol is utterly misguided.

Trying to fix your symptoms by “fixing” something that wasn’t actually causing your symptoms in the first place is not likely to result in much benefit. (This especially applies to things like “adrenal glandulars”, hydrocortisone prescriptions, and “adrenal support supplements.”)

In my experience, many of my fellow health practitioners who wish to believe in “adrenal fatigue” are angered by this assertion (even though the scientific evidence clearly supports it). But apart from them, generally speaking, most people I work with are alleviated to hear this and say something to the effect of “well that explains why I haven’t gotten very good results from trying to treat my adrenals.”

The reason adrenal fatigue focused treatments typically don’t result in profound benefits is simple: Because they’re trying to fix something that isn’t actually the cause of your problems.

By the way, the research also shows that giving patients with chronic fatigue syndrome hydrocortisone to raise their cortisol levels works no better than placebo in alleviating symptoms.[ii] That’s why this type of treatment was abandoned long ago by the vast majority of endocrinologists – because the science overwhelmingly doesn’t support its effectiveness.

Nevertheless, it’s always smart to normalize your hormones, and that can potentially help in recovery for some people. But my real goal here is simply to:

- Debunk the concept of “adrenal fatigue” so that people stop wasting their time and money trying to fix their fatigue and increase their energy levels by working on their adrenals or cortisol levels (i.e. taking adrenal support supplements, resting, eating special “adrenal diets”, or actually taking cortisol hormones in the form of adrenal glandulars or hydrocortisone medication.)

- Provide a scientifically accurate answer to the question of what is REALLY causing low morning cortisol levels (rather than the pseudoscientific answer of “adrenal burnout due to chronic stress.)

With that in mind, let’s talk about what really causes low morning cortisol levels, so that if you do want to know why your morning cortisol levels are low and how to fix it, you can do that.

In the next section, I will go over more than 20 factors known to cause (or be associated with) low morning cortisol levels. Virtually all of the factors that lower morning cortisol levels fall into the following 5 categories.

What most people who have low morning cortisol levels actually have is some combination of:

- A timing shift of their circadian rhythm of cortisol secretion, i.e. a “flattened diurnal curve” of cortisol. This means that they have less cortisol being produced in the morning and more being produced in the evening/night. This is by far the most common cause of low morning cortisol levels.

- Something impairing cortisol synthesis. This may be toxins interfering with enzymes involved in cortisol synthesis or micronutrient deficiencies in nutrients needed for synthesis of cortisol. (This is not yet backed by a large amount of evidence, and likely is only occurring in a minority of people.) Many common over-the-counter and prescription medications also are known to affect cortisol levels, such as many antidepressants, anti-anxiety drugs, blood pressure drugs, anti-inflammatory drugs, many pain drugs, etc.

- Simple measurement errors on the test. (Note: This is not a cause of your body having low cortisol levels, but a cause of why a test gives a false impression that your cortisol levels are abnormally low when they are actually normal.) There are a few simple and common errors when taking morning cortisol saliva tests that will the false impression of low morning cortisol levels. (All of these are common factors that will result in a lower cortisol level on your test. Importantly, these are simply measurement errors – not any actual inability of your adrenals to produce enough cortisol.)

- Taking the test too late in the morning.

- Taking the test after a poor night of sleep.

- Taking the test on an off day from work instead of a work day.

- Psychological states and psychosocial factors can influence cortisol levels. Also, factors that relate to one’s perception of stress, sense of self, coping ability, and more can influence cortisol levels.

- A brain that is intentionally down-regulating cortisol levels (often as a result of inflammatory or immune processes). This means that the brain is intentionally sending signals to the adrenals to decrease cortisol output and it’s NOT because the adrenals are “burned out.”

With these five overarching mechanisms now in your mind, let’s now examine the specific factors shown by the research to cause low morning cortisol levels or be associated with a flattened diurnal cortisol curve…

However, if you truly do have a flattened diurnal cortisol curve (low morning levels and high evening levels), it’s certainly a good idea to understand what causes this hormonal abnormality and how to fix it.

There are numerous lifestyle factors (many of which are very common) that will cause low morning cortisol levels.

The 20 Real Causes of Low Morning Cortisol Levels

1. Night Owl Chronotype (I.e. Staying Up Late)

Several studies have now shown that just being a night owl – no chronic stress, no symptoms, no burnout, no fatigue necessary – can cause morning cortisol levels that would get people diagnosed with “adrenal fatigue” (by a practitioner who believes in “adrenal fatigue.”)

Let me say this another way to illustrate how huge of a factor this is…

Let’s say you take a bunch of perfectly healthy people (i.e. no chronic stress, no burnout/fatigue/exhaustion) and organize them into two groups and then test their cortisol levels:

Group 1 – they go to sleep and wake up early (morning types)

Group 2 – they go to bed late and wake up late (night owls)

Even though all of these people in both groups are perfectly healthy and not stressed at all, the night owls will have dramatically lower morning cortisol levels compared with the morning types. Many of them could get diagnosed with “adrenal fatigue” based on their morning cortisol levels, even though they are perfectly healthy, not stressed and have no symptoms whatsoever.

Even though all of these people in both groups are perfectly healthy and not stressed at all, the night owls will have dramatically lower morning cortisol levels compared with the morning types. Many of them could get diagnosed with “adrenal fatigue” based on their morning cortisol levels, even though they are perfectly healthy, not stressed and have no symptoms whatsoever.

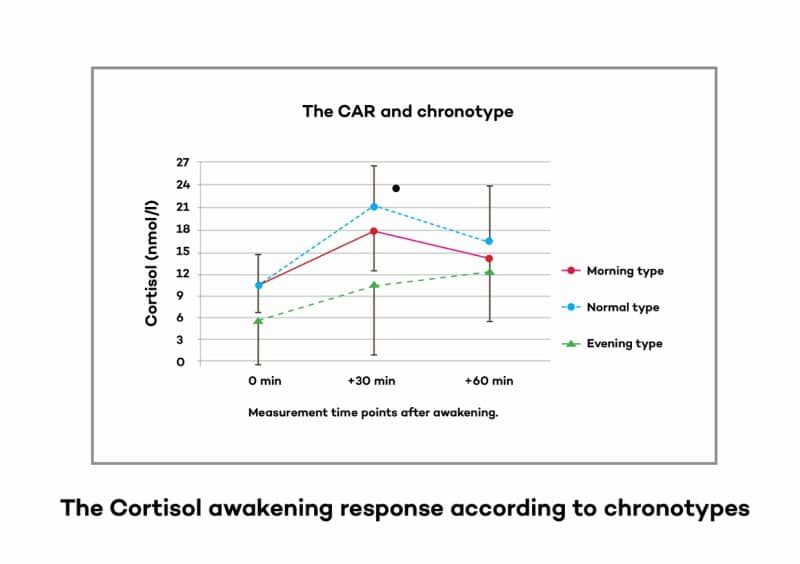

You can see here from the following graph how one key study showed that night owls (evening types) who are perfectly healthy, non-stressed and non-symptomatic have the same exact low morning cortisol levels that are claimed to be caused by “adrenal burnout.”[28]

This isn’t “adrenal burnout” – it’s just the result of going to sleep late because you’re a night owl.

Numerous other studies have also confirmed this finding.[29],[30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35]

Here’s a screenshot of the cortisol graph from one study that found almost HALF the morning cortisol levels in people who were night owls types compared to morning types.[36]

Again, please note that just this one trait ALONE – being a night owl – is often enough to cause morning cortisol levels to test below the normal range for cortisol.

Just this one factor alone could get many of the people in this study diagnosed as having “adrenal fatigue” or “complete adrenal burnout” (by people who believe in adrenal fatigue) even though the people in this study are perfectly healthy and have no symptoms at all! They are just night owls, but don’t have burnout/exhaustion or fatigue.

2. Lack Of Morning Light Exposure (Due To Poor Circadian Rhythm Habits, And/Or Living In A Place With Long Months Of Low Sunlight/Overcast Skies)

As the last factor hinted at, factors that disturb the circadian rhythm have a huge impact on the circadian profile of cortisol. Since cortisol levels are in sync with the brain’s circadian clock, the levels of cortisol at different times of the day will be altered by any input that disrupts the circadian rhythm.

One other important factor that disrupts our circadian clock in our brain – chronically, for the majority of people in the modern world – is not enough bright light exposure during the daytime and especially the morning.[37],[38],[39],[40]

We spend our days indoors in dim light conditions, and most of us do not do the vitally important task of getting bright outdoor light in our eyes within the first hour of the day. Our circadian rhythm – and morning cortisol levels – depend on this in a big way.

For example, it is known that seasonal affective disorder (which is caused by low light exposure due to living in an overcast or low-light climate during the winter months) leads to profound depression, fatigue, apathy, and other symptoms. It also causes low cortisol levels in many SAD sufferers. And it is known that bright light therapy can both correct the cortisol disturbance and correct the symptoms of SAD.[41], [42]

3. Night Eating

Keeping with the same theme as the above two factors, one other factor known to disturb the circadian rhythm is eating late at night.

Sure enough, research has also shown that the simple habit of late night eating will cause lower morning cortisol levels.[43],[44]

4. Excess Body Fat (I.e. Being Overweight)

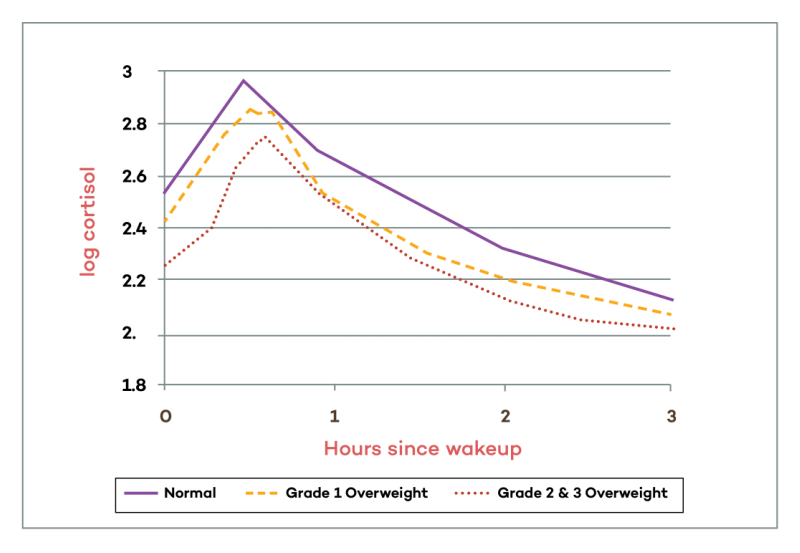

Research has shown that the more overweight someone is, the lower their morning levels of cortisol will be.[45]

Here is the graph from the key study on this topic:

You can see clearly that being slightly overweight causes a slight lowering of morning cortisol, and being significantly overweight causes an even lower peak in morning cortisol levels.

5. Nutrient Deficiencies

A large amount of vitamins and nutrients are required for the mitochondria to carry out all its metabolic processes including the cortisol production pathway.

A large amount of vitamins and nutrients are required for the mitochondria to carry out all its metabolic processes including the cortisol production pathway.

A particular study done on vitamin A deficient rats saw a marked decrease in in glucocorticoid production “even at the mildly deficient stage” (Juneja, Murthy, and Ganguly, 1966) whilst another saw cortisol production fall to a quarter of that of the control group when deficient in vitamin E.

Also note that these nutrient deficiencies are extremely common.

In addition, studies have found that consuming with multivitamin supplements can increase morning cortisol levels.[46]

Niacin derivatives, vitamin C, folic acid, pantothenic acid, biotin, calcium potassium, zinc and iron are all compounds that can potentially affect cortisol.

The evidence here is not overwhelmingly strong, but based on the existing evidence, it is certainly reasonable that a deficiency in various nutrients involved in cortisol synthesis may be a contributing factor for some people.

Recent evidence suggests that dietary intake of vitamins, in particular the B-vitamins including B6, B9 and B12 may have a number of positive effects on mood and stress. Given the effects of stress on a range of biological mechanisms including the endocrine system, it could be reasonably expected that multivitamin supplementation may also affect markers of these mechanisms such as diurnal cortisol secretion.

In the current double-blind placebo-controlled study 138 adults (aged 20 to 50 years) were administered a multivitamin containing B-vitamins versus placebo over a 16-week period. Salivary cortisol measurements were taken at waking, 15-min, 30-min and at bedtime, at baseline, 8-weeks and 16-weeks. Perceived Stress (PSS) was measured at baseline, 8-weeks and 16-weeks, while blood serum measures of B6, B12 and homocysteine (HCy) as well as red cell folate (B9) were also collected at these time points.

A significant interaction was found between treatment group and study visit for the Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR). Compared to placebo, at 16-weeks multivitamin supplementation was found to be associated with a near-significant trend towards an increased CAR. No significant differences in PSS were found between groups, with PSS increasing in both groups across the course of the study. Red cell folate was found to be significantly correlated with the CAR response at 16-weeks while HCy levels were not found to be associated with the CAR response, although HCy significantly correlated with waking cortisol levels at 8-weeks. A possible interpretation of the elevation in CAR associated with multivitamin supplementation is that this represents an adaptive response to everyday demands in healthy participants.

6. High Levels Of Depression (Major Depressive Disorder) And/Or Low Level Of Anxiety, And/Or High Perceived Suffering

Some studies show a link with higher levels of depression (major depressive disorder) and lower morning cortisol levels. (Though these findings are very mixed, and many studies show normal cortisol levels or even high cortisol levels. And it depends on the specific subtype of depression. In contrast, higher anxiety levels are associated with elevated morning cortisol levels.[47]

7. Rumination And Neuroticism

Rumination and neuroticism – both of which are contributing factors to depression – are also related to lower morning cortisol levels.[48],[49],[50],[51]

8. Helplessness/Hopelessness, Low Self-Esteem, And Low Perceived Coping Ability (Including Low Social Support And Low Psychosocial Resources)

Another factor that can lead to lower morning cortisol levels is perceived suffering. If you perceive yourself as suffering – especially if you also perceive yourself to have little ability to do anything about it – you are more likely to have low morning cortisol levels.

Another factor that can lead to lower morning cortisol levels is perceived suffering. If you perceive yourself as suffering – especially if you also perceive yourself to have little ability to do anything about it – you are more likely to have low morning cortisol levels.

“Self-reported higher anxiety levels positively correlated with steeper diurnal cortisol patterns, possibly showing body’s natural response to external stress. On the other hand, self-reported depressive symptoms at a severe level and higher suffering levels are related to abnormal stress reactivity seen as flatter diurnal cortisol patterns.”[52]

There are also several psychological traits and states that can contribute to low morning cortisol levels. Low self-esteem, high degrees of hopelessness and low perceived ability to cope with the demands on oneself are all linked with decreased morning cortisol levels.[53],[54]

In general, these correlations are small (in contrast to circadian rhythm and sleep disruptions, for example). Many studies that have examined personality traits and psychological states as they relate to cortisol levels find only small effects or no significant effects for most variables.

9. Cynicism

Cynicism (which speaks to personality traits and orientation to the world) is also linked with low morning cortisol levels.[55]

10. Medications That Affect Cortisol Levels (Many Antidepressants, Anti-Anxiety Drugs, Opioids, etc.)

Several different types of prescription and over-the-counter drugs can affect morning cortisol levels.[56]

Several different types of prescription and over-the-counter drugs can affect morning cortisol levels.[56]

One example is some types of antidepressants.

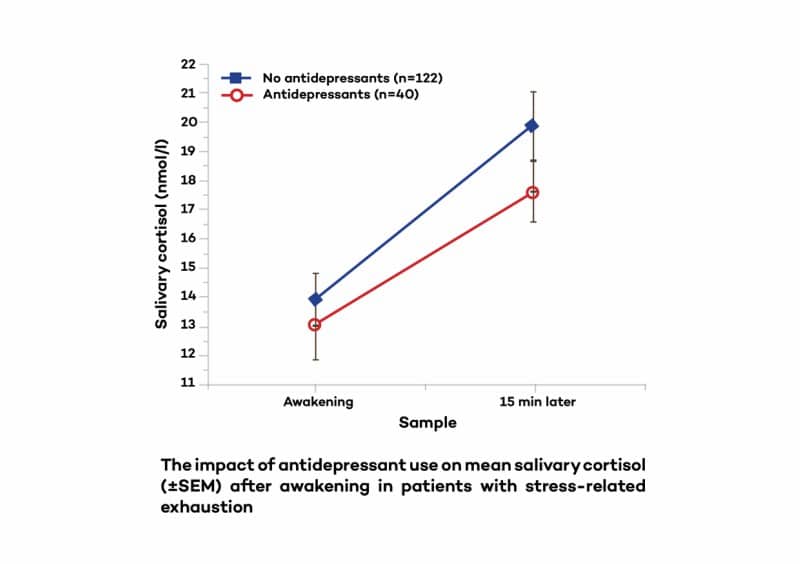

Here is a graph from one study that showed a lower peak in morning cortisol in people on antidepressants.[57]

This graph illustrates the morning cortisol awakening response in a group of people with stress-related exhaustion, that only differed based on whether they were on antidepressants or not.

Again, both groups had stress-related exhaustion, but the group on antidepressants had a significantly lower morning cortisol level.

Other medications that can affect (or can potentially affect cortisol levels) include:

- Xanax[58]

- Aspirin[59]

- Tylenol/acetaminophen[60]

- Gabapentin[61]

- Opioids[62],[63],[64]

- Some blood pressure lowering drugs[65]

- Some anti-inflammatory and painkilling drugs, like Celebrex [66]

11. Recent Loss Of A Partner Or Social Isolation/Loneliness

Another factor that is associated with lower morning cortisol levels is loneliness and/or recent loss of a partner.[67],[68]

12. Ethnicity

This has not yet been extensively studied, but research does indicate that African Americans and Hispanics tend to have lower morning cortisol levels versus Caucasians.[69]

This has not yet been extensively studied, but research does indicate that African Americans and Hispanics tend to have lower morning cortisol levels versus Caucasians.[69]

So if you are African American or Hispanic, this is a factor to consider in your morning cortisol level tests. It is totally normal for you to have lower cortisol levels in the morning relative to caucasians. This is also significant because established normal ranges for lab tests may be predominately based on cortisol levels in Caucasians (since they represent a much higher proportion of the population.)

13. Low Physical Activity Levels/Being More Sedentary

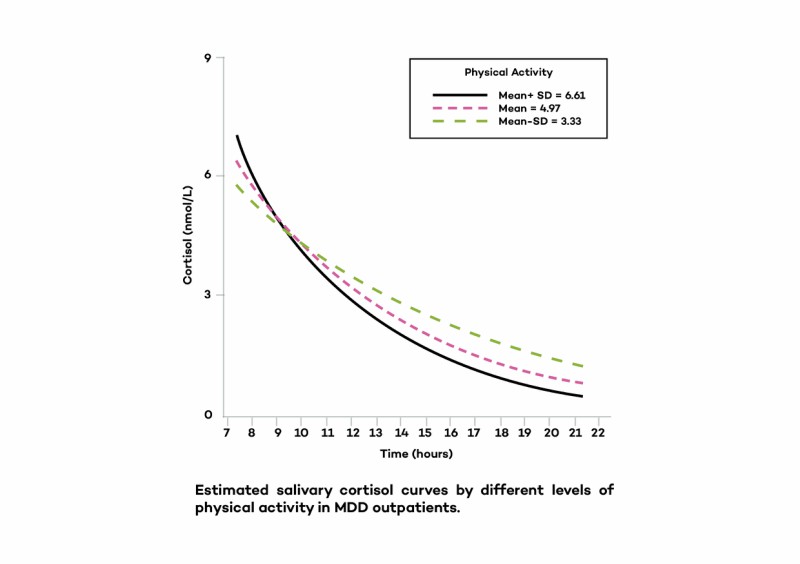

Several studies have shown that lower physical activity levels during the day can cause a lower morning peak in cortisol levels.[70]

Here is one study that looked at people with major depression to examine how their physical activity habits related to their cortisol patterns.

Higher physical activity led to a more pronounced rise (awakening response) and fall of daily cortisol levels (which is a good thing). On the other hand, being more sedentary was associated with a flatter diurnal cortisol curve (lower morning cortisol and higher evening cortisol).

14. Anticipation Of Low Demands In The Upcoming Day

Simply having a day off work (or not having a job) instead of working.

Simply having a day off work (or not having a job) instead of working.

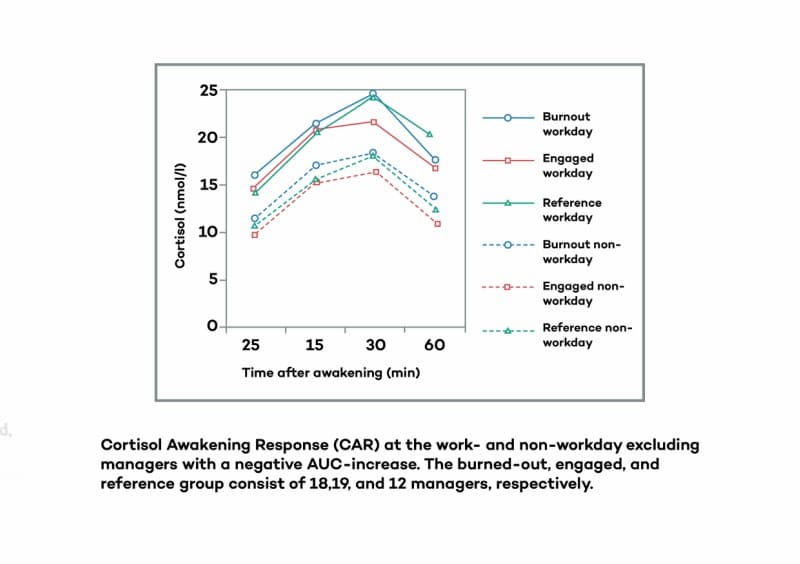

Research has even shown that morning cortisol awakening response can be high one day and low the next, as a simple function of whether or not someone has work that day or it’s a weekend.

Specifically, having work (and thus a greater anticipated demand of the day) will lead to a higher cortisol peak, and having a day off work leads to a lower cortisol peak.[71]

As you can see from the above graph, simply having a day off dramatically lowered morning cortisol awakening response in all groups. In fact, levels from workday to non-workday vary by close to 50% in the same person! I.e. Morning cortisol levels on work days can be close to 50% higher than non-workdays.

As you can see from the above graph, simply having a day off dramatically lowered morning cortisol awakening response in all groups. In fact, levels from workday to non-workday vary by close to 50% in the same person! I.e. Morning cortisol levels on work days can be close to 50% higher than non-workdays.

Importantly, this change occurred from one day to the next in the same individuals, and thus contradicts the notion that morning cortisol levels are an accurate biomarker of one’s adrenal function. Levels vary dramatically from one day to the next just by one single variable whether you have work that day or not (or other variables like how well you slept the night prior to the test).

(Side note: This also represents a significant confounding variable in cortisol testing, because people doing at-home tests take measurements on non-work days, they will measure with significantly lower cortisol than on work days. Also, for people who don’t work at all, they may test dramatically differently compared to if they had a job. This factor is never controlled for on cortisol tests done by clinicians. Ideally, there should be separate “normal ranges” of morning cortisol levels for working people vs. non-working people because normal ranges for these groups are very different. And people should be instructed to do cortisol tests at home only on work days and not non-work days.)

Key point: Lower perceived demands of the day – from either not having a job or simply having a day off from work that day – leads to dramatically lower morning cortisol levels. This can occur from one day to the next and shows that cortisol levels are not a stable reflection of adrenal function, but are dynamic in responding the environment from one day to the next.

15. Lower Socioeconomic Status

Lower vs. higher socioeconomic status is another factor that can contribute to lower morning cortisol levels.[72] The exact reasons why this occurs are not fully understood, but I suspect it may relate to the previous factor about perceived stress/hopelessness and low perceived ability to cope with the demands on oneself.

Lower vs. higher socioeconomic status is another factor that can contribute to lower morning cortisol levels.[72] The exact reasons why this occurs are not fully understood, but I suspect it may relate to the previous factor about perceived stress/hopelessness and low perceived ability to cope with the demands on oneself.

It may also relate to the previous factor, since rates of unemployment are likely higher in low socioeconomic groups, and not having a job (low anticipation of demands in the upcoming work day) is linked with lower morning cortisol levels.

16. Psychological Trauma, PTSD, Or Childhood Adversity

One of the factors that has been consistently linked with lower morning cortisol levels is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[73]

One of the factors that has been consistently linked with lower morning cortisol levels is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[73]

Both childhood trauma and PTSD are associated with lower morning cortisol levels and a flatter diurnal cortisol curve (lower morning cortisol and higher evening cortisol). Having a childhood with lots of adversity, and even having a childhood caregiver with low self-esteem are all also associated with low morning cortisol levels in adulthood.

More than reflecting the current stress load on the body or the adrenals’ ability to produce enough cortisol, this likely has to do with how early life stress or past-trauma can re-wire the stress response systems of the body. Psychological trauma can have a lasting impact on HPA axis function and leave its imprint by essentially re-wiring the way the brain regulates the stress response, and this is reflected in cortisol levels.

17. Genetic Influences/Inheritance

There is also a sizable body of evidence in both animals and humans showing that different groups of people have different baseline cortisol level that they are born with – not as a result of anything they’ve done or not done.[74],[75],[76]

There is also a sizable body of evidence in both animals and humans showing that different groups of people have different baseline cortisol level that they are born with – not as a result of anything they’ve done or not done.[74],[75],[76]

It’s also been shown that low baseline cortisol levels can be passed on from one generation to the next. I.e. If your mother had lower baseline cortisol levels, you may have it as well, just due to genetic influences.

18. Toxins

While still somewhat speculative in showing a direct link in humans with low cortisol levels, there is research in animals and humans showing that several different types of chemicals in the environment have been shown to interfere with enzymes involved in cortisol synthesis.

While still somewhat speculative in showing a direct link in humans with low cortisol levels, there is research in animals and humans showing that several different types of chemicals in the environment have been shown to interfere with enzymes involved in cortisol synthesis.

Given that we know we are being exposed to these chemicals – and tests have shown these chemicals present in significant quantities in most humans in the Western world – it is reasonable to believe that exposure to these compounds can at the very least be a small contributor to why someone may have lower cortisol levels.

Importantly, I want to distinguish between the concept of “chronic stress wearing out the adrenal glands” vs. chemicals interfering with specific enzymes involved in cortisol production. To put it simply: Running out of gas is very different from a traffic jam on the freeway.

In this case, we’re talking about the adrenals having a “traffic jam” of sorts, with regard to the biochemical processes involved in cortisol synthesis.

The story however, is not as simple as simply saying “exposure to these compounds decreases cortisol production”, as distinctions within each study have to be made between low and high doses, acute and long term exposure, whether the individual affected is male or female and whether the measurement of cortisol is a baseline reading or one from stress provocation.

The picture is further muddled when we see elevated levels of cortisol in some studies and, within others, a drastic reduction. It cannot be said whether all of these toxins produce low cortisol levels in all individuals at all levels of exposure but it is clear that serious hormonal disruption is occurring in many circumstances, often affecting cortisol production.

Here are some of the relevant things to know about toxins and cortisol:

- Particular toxins such as glyphosate (Roundup) and other pesticides, fungicides, BPA found in plastics and heavy metals have been shown to interfere with cortisol levels in the blood. [77],[78],[79],[80],[81]

- One study showed that exposure to arsenic decreased activity of the enzyme, 3β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase which is a key mitochondrial enzyme used in the first step of the pathway converting cholesterol into cortisol.[82]

- Another study observed the inhibiting effect of azole fungicides upon an enzyme called steroid 21-hydroxylase (CYP21).[83] This enzyme is found within specific cortisol producing cells in the adrenal glands and its functioning is key to the normal production of cortisol and, as you can guess, presence of the azole fungicides could disrupt production and lead to hypocortisolemia.

- People who live in very agricultural or industrial parts of the country may be exposed to unhealthy levels of these azole fungicides and pesticides like glyphosate.[84]

Exposure to BPA, pesticide residues, and heavy metals is ubiquitous. And again, it is known that significant amounts of these compounds in the body can hinder the enzymes needed for cortisol synthesis (among many other effects.)

19. HPA Axis Hypoactivity (Low Cortisol Levels) Is A CONSEQUENCE Of Oxidative/Nitrosative Damage And Over-Activation Of Immune/Inflammatory Pathways

Chronic inflammation will eventually lead to suppression of cortisol levels. This is not due to the body’s adrenal glands wearing out and being unable to produce enough cortisol, but rather is due to the body intelligently trying to facilitate inflammatory processes against inflammatory insults.

Chronic oxidative stress (from junk food, mold, toxin exposure in food/water/air/personal care products, etc.) can also cause the body to intentionally suppress cortisol levels. And immune insults – like chronic infections, and poor immune function – can also lead to the body intentionally suppressing cortisol levels.

Combinations of chronic inflammation, oxidative damage, and immune activation (e.g. junk food, mold, infections, toxin exposure) are likely especially effective at making the body decrease cortisol output.

Cortisol is anti-inflammatory and suppresses immune function. So basically these things oppose each other. If the body is trying to prioritize increasing inflammatory and immune responses, it will tend to decrease cortisol levels.

In people with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome specifically, research has shown that when people have low cortisol levels, it is likely just a consequence of increased inflammation and immune activation.[85]

One important study describes this phenomenon as an important way the body adapts. I.e. The body intentionally lowers cortisol as an adaptive and intelligent response to support proper immune system and inflammatory system functions:

“While the terms adrenal fatigue/exhaustion may serve to point out reduced adrenal production of cortisol and DHEA, the adaptive changes are most often initiated within and propagated by the hypothalamus and pituitary. In fact, some researchers believe that the adaptation by the HPA axis is a protective device to ensure long-term survival by preventing chronically high cortisol levels from suppressing immune function and increasing catabolic pathways.”[86]

(Knowing this, it’s important to understand that the goal in such a scenario is not simply to take cortisol boosting compounds or to treat the adrenal glands, but instead to address the factors causing chronic inflammation and immune overactivation.)

20. Poor sleep (or lack of sleep)

This, along with the two circadian rhythm related factors, are the absolute biggest causes for the vast majority of people who have low morning cortisol levels.

This, along with the two circadian rhythm related factors, are the absolute biggest causes for the vast majority of people who have low morning cortisol levels.

Several studies have shown that simply sleeping poorly will cause a lower peak in morning cortisol.[87],[88],[89]

This may be from not having enough hours of sleep or from sleep disorders or sleep apnea, or simply from poor circadian rhythm and sleep hygiene habits that result in poor “sleep efficiency.”

Importantly, it’s not just the number of hours you sleep, but also the quality of your sleep (i.e. sleep efficiency) that affects Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal function and cortisol levels.[90]

Sleep efficiency is basically how restful and regenerative each hour of sleep is. I.e. It’s possible to sleep 8 hours with high sleep efficiency or sleep 8 hours with poor sleep efficiency – and this makes a huge difference to your health and hormonal function.

There is no need for chronic stress over months/years to exhaust the adrenals – a few nights of poor sleep will cause the same exact cortisol abnormality that some people think is “adrenal fatigue.”

Moreover, in case you would still be inclined to try to explain things through the lens of “adrenal fatigue” theory and say that the poor sleep is exhausting the adrenals, it’s worthwhile to note that the research has actually shown that even a single night of poor sleep will cause low morning cortisol, and that simply correcting the sleep can immediately resolve the cortisol pattern back to normal, within just days.[91] In other words, these changes reflect a dynamic daily shifting of cortisol output in response to what’s going on day-to-day, and the cortisol levels are NOT a stable and accurate diagnostic of the stage of “adrenal burnout.” So there is no need to invoke any theories about the adrenals getting “fatigued” in order to explain low morning cortisol levels – it can simply be an acute response to poor sleep or disrupted circadian rhythm (or having a day off work, or many of the other factors listed in this article).

For example, day-to-day sleep variations and something as simple as prior day napping can have a huge impact on cortisol levels: “Both daily variations in sleep behaviors and ongoing sleep disturbance and fatigue are associated with a disrupted cortisol rhythm. In contrast, prior-day napping is associated with a more robust cortisol rhythm.”[92]

In other words, morning cortisol levels change from one day to the next according to how much sleep you get. Sleep more and take a nap in the afternoon and you can sometimes go from abnormal cortisol levels one day back up to normal the next day.

Another study in people with depression supports this view as well. They found that it is only those people who have trouble sleeping that have low morning cortisol – i.e. the people with depression who don’t have sleep problems have normal cortisol levels.[93] Again, this suggests that it is the sleep issues that are causing the cortisol abnormalities. (I.e. Contrary to the explanation you’d hear from advocates of adrenal fatigue, this study makes it clear that the low morning cortisol isn’t the “cause” of the symptom of depression – the low cortisol levels are simply an epiphenomenon that occurs in those depressed people who don’t sleep well, as a SYMPTOM of the poor sleep.)

One study on people with Burnout Syndrome went so far as to say:

“The data supports the notion that sleep impairments are causative and maintaining factors for this condition.”[94]

Another study in chronic fatigue syndrome concluded:

“Neuroendocrine abnormalities (i.e. low morning cortisol) reported to be characteristic of chronic fatigue syndrome may be merely the consequence of disrupted sleep and social routine.”[95]

Cortisol levels are NOT an accurate reflection of the degree of chronic stress a person is under (as we’ve seen in the previous sections), but they ARE a pretty good reflection of whether or not a person is getting enough deep restful sleep. (Not because sleep “burns out the adrenal glands”, but because it disrupts the timing of cortisol release during the day.)

The simple fact is that this one factor – poor sleep – is, by itself, enough to cause low morning cortisol levels that could get you diagnosed with “adrenal fatigue.”

Given how common sleep problems are in people with Burnout, Stress-Related Exhaustion, and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, it’s actually a wonder that most people with these conditions still don’t have low morning cortisol levels.

Along with being a night owl chronotype, these two factors alone – even without all the other factors listed above – are easily enough to cause low enough morning cortisol levels to get a person diagnosed with “adrenal fatigue.”

But contrary to the views of “adrenal fatigue” proponents, the solution to this isn’t to take adrenal support formulas or take cortisol (from hydrocortisone or adrenal glandulars) – it’s to correct the circadian rhythm and sleep patterns.

Now that you know the major causes of low morning cortisol levels (and a flattened diurnal cortisol curve), let’s talk about how to FIX this issue…

How To Fix Your Low Cortisol Levels

Now that we’ve covered the main causes of low morning cortisol levels, let’s talk about how to fix it. In essence, this comes down to simply correcting the factors causing the low cortisol levels in the first place. In some of these cases this is very simple and quick, and in others, much more complex.

Step 1 – First Make Sure You Did The Test Correctly And That You Truly Do Have Low Cortisol Levels

First, make sure that you actually do have low morning cortisol levels, and it was not a mistake in  testing. As you’ve seen, there are several different testing errors that can get someone falsely diagnosed with low morning cortisol levels.

testing. As you’ve seen, there are several different testing errors that can get someone falsely diagnosed with low morning cortisol levels.

- If you did a one-time measurement of cortisol (as some tests do), this is not a valid diagnostic measure. Valid cortisol measurement requires you to take 4 cortisol measurements over the course of the first few hours of the morning.

- If you did your previous cortisol test on a weekend (or non-work day), do the test again on a work day. You may not have low morning cortisol at all, but you may simply have tested it on an off day from work, and thus had much lower cortisol levels than is normal for you on work days.

- If you got a poor night of sleep the night before testing your cortisol levels, take another test after a good night of sleep.

- If you did not take your first cortisol measurement within the first 30 minutes of awakening, your results may not be valid. Do the test again, and make sure to get the time of saliva samples absolutely correct. Waiting too long after awakening to take the saliva samples can result in a false diagnosis of low cortisol levels when your cortisol levels are actually normal.

(Note: If you have extremely low cortisol levels at all times of the day – not just slightly low cortisol levels in the morning – and you have symptoms like loss of appetite, loss of body weight, dark spots developing on your skin, etc., please see a physician and get checked out for Addison’s disease).

Assuming your test is valid and you truly do have low morning cortisol levels, then go on to Step #2 on how to fix the factors that cause low morning cortisol levels.

Step 2 – Fix The Factors That Cause Low Morning Cortisol Levels

Now, let’s assume that there are no errors in testing, and you truly do have low morning cortisol levels and/or a flattened diurnal cortisol curve (low morning cortisol and higher evening cortisol).

Remember, it is almost always the case that a person doesn’t’ have any actual inability of their adrenals to pump out enough cortisol. So the goal is not to heal the adrenals, with the idea that would fix your cortisol levels. The goal here is two-fold: 1. To increase morning cortisol release, and 2. To decrease evening/night cortisol levels.

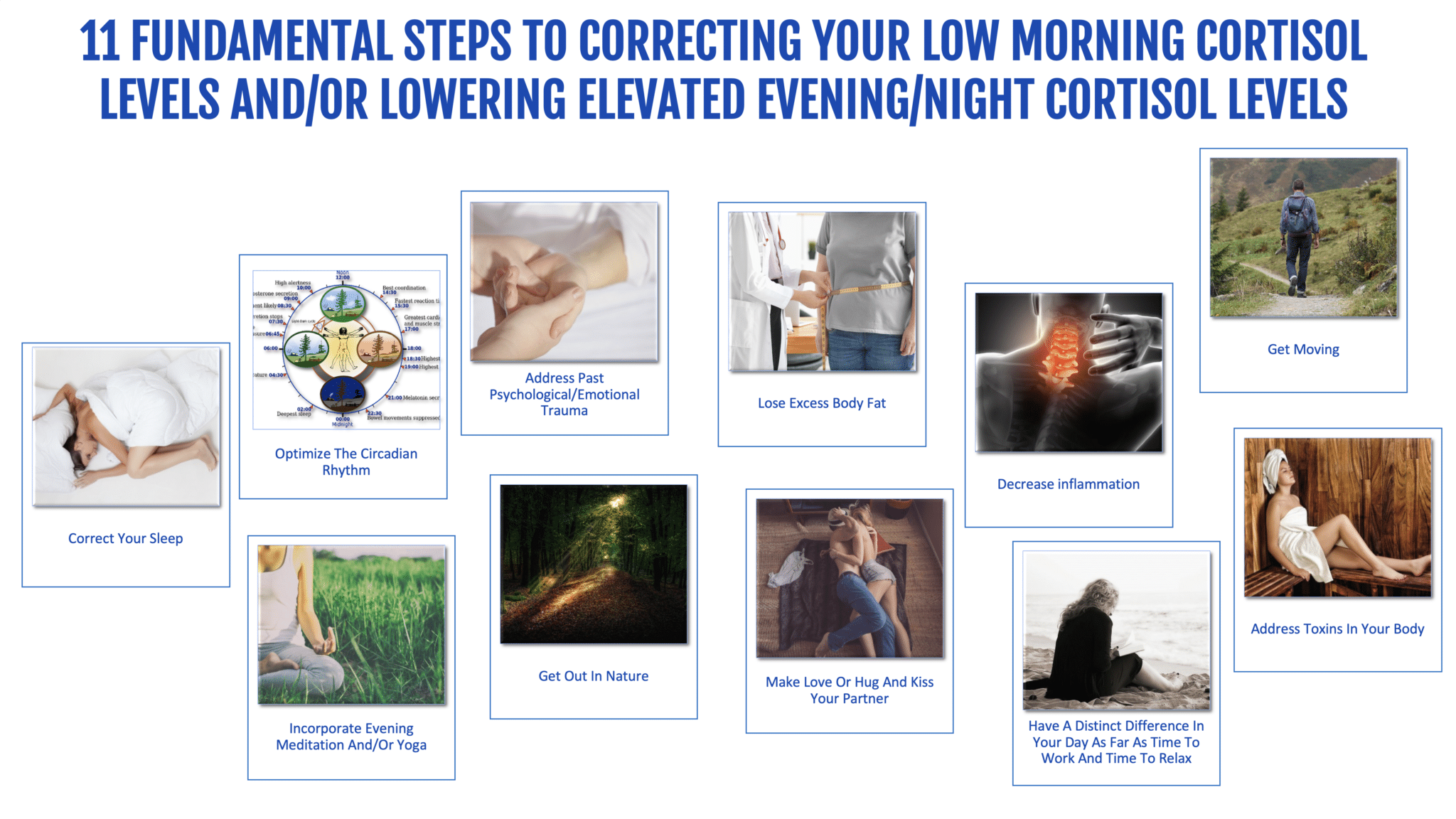

Here are the fundamental steps to correcting your low morning cortisol levels and/or lowering elevated evening/night cortisol levels:

- Optimize Your Circadian Rhythm. Here are some of the strategies I teach in The Energy Blueprint program to help you do this:

- Get bright light within the first 30 minutes after waking

- Shift bedtime and wake time earlier to shift away from a night owl rhythm

- Block artificial light at night with blue blocking technology (and ideally, blue/green blocking glasses)

- Consistently go to bed and wake up at the same time

- Consume your last bite of food no later than 2 hours before you sleep (and ideally earlier)

- Get more bright outdoor light during the day

- Decrease inflammation and oxidative damage at the cellular level. This is obviously a complex one that really involves deep and systematic nutrition and lifestyle changes, and thus can’t be summarized in a few sentences. But the basic gist of this is: Consume anti-inflammatory foods, get rid of inflammatory foods, address gut permeability, lower your exposure to heavy metals and inflammatory toxins in the food/water/air supply and your personal care products, and follow the lifestyle strategies outlined above around circadian rhythm, sleep, nutrition, and other lifestyle and psychological factors. (If you want a comprehensive and step-by-step plan to do all of this in the fastest and most powerful way possible, get The Energy Blueprint 60-day program.)

- If you are overweight, adopt systematic nutrition and lifestyle changes to lose excess body fat.

- Talk to your doctor about the possibility of weaning off any medications that affect HPA axis function. This includes (but is not limited to) many antidepressants, Xanax, Opioids, many anti-inflammatories, many painkillers, and blood pressure lowering medications, among others.

- Address past psychological/emotional trauma. This is a complex one and there are many different approaches to doing this. A few recommendations and possible paths:

- Do psychotherapy (e.g. CBT, hypnotherapy, or other forms of talk therapy) or alternative psychotherapeutic methods (e.g. EFT, trauma-release movement therapies, etc.)

- Start a dedicated daily meditation or mindfulness practice

- Volunteer for MAPS to be a part of one their studies using MDMA- or psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy. The results from the studies on people with PTSD using these methods have been incredible.

- Consider working one-on-one with a trauma release expert. (I highly recommend Niki Gratrix). I have heard amazing feedback from members of the Energy Blueprint program about working with Niki one-on-one.

- If you work a desk job or don’t do exercise (and you’re mostly sedentary), get MOVING! Start with a foundation of gentle movement (e.g. walking, yoga, qigong, pilates, dance) and add in higher intensity exercise (interval training, endurance exercise, and/or weight training) multiple times a week in accordance with your fitness levels.

- Have an evening meditation, mindfulness, qi gong, or yoga practice. [96],[97],[98] There are dozens of health benefits associated with these practices, and lowering cortisol levels is just one such benefit.

- Make love or hug and kiss your partner (if you have one) in the evening. Oxytocin helps decrease cortisol and prevents excessive increases in cortisol from mild stressors.[99] And oxytocin is released in our bodies in response to physical touch, affection, and sex.

- Get out in nature during the afternoon/evening. Nature – or “forest bathing” as much of the research refers to it – has a profound effect on numerous systems of your body, including cortisol levels. It can be very effective in lowering cortisol levels in the evening. [100]

- Address potential toxins in your body like heavy metals, BPA, pesticides, etc. that are known to interfere with cortisol levels. This includes:

- Good nutrition habits

- Using non-toxic personal care

- Using non-toxic kitchen products

- Getting a high-end water filter to drink truly pure water

- Using nutrition and lifestyle strategies to support liver health

- Using more aggressive detox protocols including sauna and various supplements designed to support detoxification

- Have a distinct difference in your day as far as time to work and time to relax.

- It is natural for cortisol to rise strongly in the morning after awakening and to be low in the evening and night. You want to facilitate and amplify this natural rise and fall through your lifestyle habits. Here’s what I mean:

- Get up and get moving – physically and psychologically. Get bright outdoor light, physically move your body, and get your brain working. Plan your day and get mentally prepared for tackling the tasks of the day. All of these will help stimulate a proper morning cortisol release.

- In the last few hours of the day, wind down and do things that are relaxing and don’t involve the same level of hustle and stress as the morning and afternoon.

- It is natural for cortisol to rise strongly in the morning after awakening and to be low in the evening and night. You want to facilitate and amplify this natural rise and fall through your lifestyle habits. Here’s what I mean:

- Correct your sleep. This is another complex one, but is perhaps the most common cause of low morning cortisol levels for most people. Thus it is also the single most powerful way to correct morning cortisol levels – sometimes within a matter of a few days or a couple weeks. If you want more details on how to start doing this, Module 1 of my Energy Blueprint program is all about this subject and gives 27 strategies to optimize circadian rhythm and sleep. (Many people report that this dramatically deepens their sleep and increases their energy within the first two weeks on the program.) Here are some powerful strategies to get you started:

- Follow the circadian rhythm strategies outlined above. This is CRITICAL for sleep quality.

- Follow the pre-bed ritual recommendations outlined above, and incorporate some combination of meditation/nature/yoga/journaling/sex in your evenings.

- Sleep in complete darkness (use blackout shades ideally, or an eye mask if blackout shades are not doable.)

- Sleep on a high-quality mattress proven to enhance sleep quality (see my podcast here).

- Get electronic devices out of your room, and/or make sure you’re not exposed to blue light or significant electromagnetic fields (which also suppress melatonin levels.)

- If you normally wake up extremely unrefreshed (and/or your partner tells you that you snore), get checked for sleep apnea. This and other sleep disorders are extremely common among people with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (over 50% of people with CFS have a sleep disorder), and they are common in people with Burnout Syndrome as well. Getting diagnosed and treated for sleep apnea (e.g. a CPAP machine) can be life-changing for some people.

- Have a relaxing pre-bed ritual for 1-2 hours before bed. This should be your time to allow your brain to turn off.

- Stop working, stop trying to solve problems, stop ruminating, and release any stress/negativity/tension of the day. Actively do things during this time period that supports this process.

- Consciously engage in positive emotional states – e.g. do gratitude journaling, laugh with a friend, watch stand up comedy or videos you find funny.

- Do a physical release (e.g. yoga/stretching/sex), and do a mental release (e.g. meditation/mindfulness).

- Do something relaxing and enjoyable like reading a book or watching a relaxing and fun movie or watch stand-up comedy or make love. Turn off your brain and body, and help everything go into relaxation and regeneration mode.

Final Words

These are the REAL reasons why people typically have low morning cortisol levels. It’s not due to chronic stress wearing out your adrenals and rendering them incapable of producing enough cortisol. It’s one or more of these factors that have shifted your cortisol rhythms and/or caused your HPA axis to regulate cortisol levels differently (i.e. less cortisol in the morning and more in the evening).

Working on your circadian rhythm and sleep habits, losing body fat (if you’re overweight), weaning off medications that disrupt HPA axis function, physical activity, correcting chronic inflammation, working on psychological health, good nutrition habits, and a powerfully relaxing and regenerative pre-bed ritual will correct low morning cortisol levels (and high evening cortisol levels) for the vast majority of people with low morning cortisol levels, often times within a few weeks.

I hope that this information will shift the paradigm around the common thinking about fatigue being caused by “adrenal fatigue” (due to chronic stress wearing out the adrenals), and that we can begin to focus our energy on fixing our symptoms by addressing real root causes.

Article Summary

The evidence does not support the “adrenal fatigue” theory.

- Chronic stress is NOT reliably associated with low cortisol levels (thus disproving the “adrenal fatigue” theory).

- The evidence does not support the claim that there is a general pattern where chronic stress (or chronic disease) leads to “adrenal fatigue” or low cortisol levels.

- Stress-Related Exhaustion and Burnout Syndrome have no clear connection to abnormal cortisol levels or adrenal function. These conditions/symptoms are clearly NOT caused low cortisol levels.

- So remember, fixing your cortisol levels won’t necessarily fix your fatigue/burnout symptoms.

- So what causes low cortisol levels? Lower morning cortisol levels are typically the result of some combination of the 20 lifestyle and environment factors mentioned above. The biggest factors in lower morning cortisol levels (i.e. the most common causes of low morning cortisol levels) are circadian rhythm disruption, being a night owl, and poor sleep.

- Secondary to that, the most common causes of lower morning cortisol levels for most people are likely to be one or more of the following factors:

- Chronic inflammation or immune activation

- Medications which interfere with cortisol (e.g. many antidepressants, Xanax, Opioids, anti-inflammatories, painkillers, and blood pressure lowering medications, etc.)

- Lack of physical activity

- Excess body fat

- Not being employed (or taking the cortisol test on a day off from work)

- Psychosocial factors: rumination, neuroticism, depression, suffering, social isolation, low self-esteem, low social support, and/or low perceived coping ability

- Genetic influences (e.g. ethnicity, family ancestry with 21-hydroxylase deficiency, or parents with history of trauma, etc.)

- Past history of trauma or childhood adversity

- You can fix your morning cortisol levels by using the above list of strategies. I suggest focusing your efforts on the following strategies:

-

-

- Optimize circadian rhythm

- Optimize sleep habits

- Decrease inflammation and oxidative stress at the cellular level

- Movement/physical activity

- Meditation/mindfulness/yoga practices in the evening

- Optimize light exposure habits

- Check with your doctor about any medications you may be using that affect cortisol levels

- If you have a history of psychological abuse/trauma, address that using the above strategies

- Adopt strategies to amplify the normal rise and fall of cortisol at the appropriate time of day

- Pre-bed ritual including strategies to directly calm the brain and nervous system using the above recommendations

-

By using the above strategies to fix your cortisol levels – i.e. by actually understanding the true causes of low morning cortisol levels and addressing them appropriately – you can potentially fix your cortisol levels in a matter of a few weeks (as opposed to the 6-12 months often claimed by “adrenal fatigue” proponents.)

References

[28] Abbruzzese EA., et al. (2014) The Influence Of The Chronotype On The Awakening Response Of Cortisol In The Morning

[29] Edwards, S. et. al., (2001), Association between time of awakening and diurnal cortisol secretory activity, Psychoneuroendocrinology 26(6):613-22 · September 2001

[30] Abbruzzese EA., et al. (2014) The Influence Of The Chronotype On The Awakening Response Of Cortisol In The Morning

[31] BM Kudielka et al. (2005) Morningness and Eveningness: The Free Cortisol Rise After Awakening in “Early Birds” and “Night Owls”

[32] Fries E., et al. (2008) The cortisol awakening response (CAR): Facts and future directions

[i]Christianson A. MD., Kresser C., (2016) Adrenal Summit Interview

[33] Oginska H., et al. (2010) Chronotype, sleep loss, and diurnal pattern of salivary cortisol in a simulated daylong driving.

[34] Polugrudov, AS., et al. (2016) Wrist temperature and cortisol awakening response in humans with social jetlag in the North

[35] Kohyama J. (2011) Neurochemical and Neuropharmacological Aspects of Circadian Disruptions: An Introduction to Asynchronization

[36] Oginska H., et al. (2010) Chronotype, sleep loss, and diurnal pattern of salivary cortisol in a simulated daylong driving.

[37]Martiny, K., et al., (2009) High cortisol awakening response is associated with an impairment of the effect of bright light therapy, Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 120(3):196-202 · March 2009

[38]Thorn, L,. et. al. (2011) Seasonal differences in the diurnal pattern of cortisol secretion in healthy participants and those with self-assessed seasonal affective disorder, Psychoneuroendocrinology, Volume 36, Issue 6, July 2011, Pages 816-823

[39] Gabel, V., et. al., (2013) Effects of Artificial Dawn and Morning Blue Light on Daytime Cognitive Performance, Well-being, Cortisol and Melatonin Levels, The Journal of Biological and Medical Rhythm Research, Volume 30, 2013 – Issue 8

[40] Figueiro, MG., et. al., (2012) Short-Wavelength Light Enhances Cortisol Awakening Response in Sleep-Restricted Adolescents, International Journal of Endocrinology, Volume 2012, Article ID 301935, 7 pages

[41] Thorn, L., et. al., (2004) The effect of dawn simulation on the cortisol response to awakening in healthy participants. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004 Aug;29(7):925-30.

[42] Clow, A., The diurnal pattern of cortisol secretion in relation to season in healthy participants and those with seasonal affective disorder.

[43] Goel N., et al. (2009) Circadian rhythm profiles in women with night eating syndrome.

[44] Goel, N., et. al. (2009) Circadian Rhythm Profiles in Women with Night Eating Syndrome, J Biol Rhythms. 2009 Feb; 24(1): 85–94. doi: 10.1177/0748730408328914

[45] Champaneri, S MD et al. (2013) Diurnal Salivary Cortisol is Associated With Body Mass Index and Waist Circumference: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

[46] Camfield, DA., et. al., (2013) The Effects of Multivitamin Supplementation on Diurnal Cortisol Secretion and Perceived Stress, Nutrients. 2013 Nov; 5(11): 4429–4450. Published online 2013 Nov 11. doi: 10.3390/nu5114429

[47] Hsiao, FH., et. al., (2010) The self-perceived symptom distress and health-related conditions associated with morning to evening diurnal cortisol patterns in outpatients with major depressive disorder, Psychoneuroendocrinology, Volume 35, Issue 4, May 2010, Pages 503-515

[48] Thorn, L., et. al., (2004) The effect of dawn simulation on the cortisol response to awakening in healthy participants. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004 Aug;29(7):925-30.

[49] V. Santen, A., et. al., (2011) Psychological traits and the cortisol awakening response: Results from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety, Psychoneuroendocrinology, Volume 36, Issue 2, February 2011, Pages 240-248

[50]Hauner, KKY., et. al., Neuroticism and Introversion are Associated with Salivary Cortisol Patterns in Adolescents, Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008 Nov; 33(10): 1344–1356. Published online 2008 Sep 21. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.07.011

[51]Sjogren, E., et. al., (2006) Diurnal saliva cortisol levels and relations to psychosocial factors in a population sample of middle-aged swedish men and women, International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, September 2006, Volume 13, Issue 3, pp 193–200

[52] Hsiao, FH., et. al., (2010) The self-perceived symptom distress and health-related conditions associated with morning to evening diurnal cortisol patterns in outpatients with major depressive disorder, Psychoneuroendocrinology, Volume 35, Issue 4, May 2010, Pages 503-515

[53] Sjogren, E., et. al., (2006) Diurnal saliva cortisol levels and relations to psychosocial factors in a population sample of middle-aged swedish men and women, International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, September 2006, Volume 13, Issue 3, pp 193–200

[54] Zilioli, S., et. al., (2016) Childhood Adversity, Self-Esteem, and Diurnal Cortisol Profiles across the Lifespan, Psychol Sci. 2016 Sep; 27(9): 1249–1265. Published online 2016 Aug 1. doi: 10.1177/0956797616658287

[55] Sjogren, E., et. al., (2006) Diurnal saliva cortisol levels and relations to psychosocial factors in a population sample of middle-aged swedish men and women, International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, September 2006, Volume 13, Issue 3, pp 193–200

[56] Granger, DA., et. al., (2009), Medication effects on salivary cortisol: tactics and strategy to minimize impact in behavioral and developmental science. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009 Nov;34(10):1437-48. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.06.017. Epub 2009 Jul 25.

[57] Sjörs A., et al. Long-term follow-up of cortisol awakening response in patients treated for stress-related exhaustion

[58] Fukuda, M., et al., (1998) Decreased plasma cortisol level during alprazolam treatment of panic disorder: a case report., Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1998 Jul;22(5):909-15.

[59] Nye, EJ., et al., (1997) Aspirin Inhibits Vasopressin-Induced Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Activity in Normal Humans, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 82, Issue 3, 1 March 1997, Pages 812–817

[60] Oskarsson A, et al., Acetaminophen Increases Aldosterone Secretion While Suppressing Cortisol and Androgens: A Possible Link to Increased Risk of Hypertension., Am J Hypertens. 2016 Oct;29(10):1158-64. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpw055. Epub 2016 May 23.

[61] Karbić VO, et al., Gabapentin-induced changes of plasma cortisol level and immune status in hysterectomized women., Int Immunopharmacol. 2014 Dec;23(2):530-6. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.09.029. Epub 2014 Oct 16.

[62] Hibel LC, et al., Individual differences in salivary cortisol: associations with common over-the-counter and prescription medication status in infants and their mothers. Horm Behav. 2006 Aug;50(2):293-300. Epub 2006 May 6.

[63] Lee, AS., et al., (2015) Opioid-induced secondary adrenal insufficiency presenting as hypercalcaemia, Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2015; 2015: 150035.

[64] Colameco, S., et al., Opioid-Induced Endocrinopathy, The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, January 2009, Vol. 109, 20-25.

[65] Dart, AM., et al., (1981) The effect of chronic propranolol treatment on Overnight plasma levels of anterior pituitary and Related hormones, Departments of Cardiology and Pharmacology, Welsh National School of Medicine and Tenovus Institute for Cancer Research, Cardiff

[66] Liu, S., et al., Celecoxib reduces glucocorticoids in vitro and in a mouse model with adrenocortical hyperplasia, Endocr Relat Cancer. 2016 Jan; 23(1): 15–25. Published online 2015 Oct 5. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0472

[67] Doane, LD., et. al., (2009) Loneliness and Cortisol: Momentary, Day-to-day, and Trait Associations, Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010 Apr; 35(3): 430–441. Published online 2009 Sep 9. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.08.005

[68] Doane, LD., et. al., (2009) Loneliness and Cortisol: Momentary, Day-to-day, and Trait Associations, Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010 Apr; 35(3): 430–441. Published online 2009 Sep 9. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.08.005

[69] Hajat, A., et. al., (2010) Socioeconomic and race/ethnic differences in daily salivary cortisol profiles: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010 Jul; 35(6): 932–943. Published online 2010 Jan 29. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.12.009

[70] Tryon WW., et al. (2004) Chronic fatigue syndrome impairs circadian rhythm of activity level

[71] Fries E., et al. (2008) The cortisol awakening response (CAR): Facts and future directions

[72]Hajat, A., et. al., (2010) Socioeconomic and race/ethnic differences in daily salivary cortisol profiles: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010 Jul; 35(6): 932–943. Published online 2010 Jan 29. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.12.009

[73] Zilioli, S., et. al., (2016) Childhood Adversity, Self-Esteem, and Diurnal Cortisol Profiles across the Lifespan, Psychol Sci. 2016 Sep; 27(9): 1249–1265. Published online 2016 Aug 1. doi: 10.1177/0956797616658287

[74] Shahili Jain, (2016) Cortisol, the Intergenerational Transmission of Stress, and PTSD: An Interview With Dr. Rachel Yehuda

[75] Genetics Home Reference, Familial glucocorticoid deficiency

[76] Genetics Home Reference, 21-hydroxylase deficiency

[77] Young, F., Edwards, V., Ho, D. and Glynn, D. (2015) ‘Endocrine disruption and cytotoxicity of glyphosate and roundup in human JAr cells in vitro’, Integrative Pharmacology, Toxicology and Genotoxicology, 1(1), pp. 12–19. doi: 10.15761/iptg.1000104.

[78] Sanderson, T.J. (2006) ‘The steroid hormone Biosynthesis pathway as a target for endocrine-disrupting chemicals’, Toxicological Sciences, 94(1), pp. 21–3. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl051.

[79] Sanderson, T.J. (2006) ‘The steroid hormone Biosynthesis pathway as a target for endocrine-disrupting chemicals’, Toxicological Sciences, 94(1), pp. 21–3. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl051.

[80] Panagiotidou, E., Zerva, S., Mitsiou, D.J., Alexis, M.N., Kitraki, E. and ekitraki (2014) ‘Perinatal exposure to low-dose bisphenol A affects the neuroendocrine stress response in rats’, Journal of Endocrinology, 220(3), pp. 207–218. doi: 10.1530/JOE-13-0416.

[81] Dyer, C.A. (2007) ‘Heavy metals as endocrine-disrupting chemicals’, in Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Springer Nature, pp. 111–133.

[82] Dyer, C.A. (2007) ‘Heavy metals as endocrine-disrupting chemicals’, in Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Springer Nature, pp. 111–133.

[83] Sanderson, T.J. (2006) ‘The steroid hormone Biosynthesis pathway as a target for endocrine-disrupting chemicals’, Toxicological Sciences, 94(1), pp. 21–3. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl051.

[84]Myers, J.P., et al., (2016) ‘Concerns over use of glyphosate-based herbicides and risks associated with exposures: A consensus statement’, Environmental Health, 15(1). doi: 10.1186/s12940-016-0117-0.

[85]Morris, G., et. al., (2017) Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Hypofunction in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) as a Consequence of Activated Immune-Inflammatory and Oxidative and Nitrosative Pathways. Mol Neurobiol. 2017 Nov;54(9):6806-6819. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0170-2. Epub 2016 Oct 20.

[86] Guilliams, TG., et al., (2010) Chronic Stress and the HPA Axis: Clinical Assessment and Therapeutic Considerations, The Standard

[87]Bozic, L., et. al., (2016) Morning cortisol levels and glucose metabolism parameters in moderate and severe obstructive sleep apnea patients. Endocrine. 2016 Sep;53(3):730-9. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-0925-6. Epub 2016 Mar 21.

[88] Späth-Schwalbe E., et al. (1992) Nocturnal adrenocorticotropin and cortisol secretion depends on sleep duration and decreases in association with spontaneous awakening in the morning.

[89] Leese G., et al. (1996) Short-term night-shift working mimics the pituitary-adrenocortical dysfunction in chronic fatigue syndrome.

[90] Bassett, SM., et. al., Sleep quality but not sleep quantity effects on cortisol responses to acute psychosocial stress, Stress. 2015; 18(6): 638–644. Published online 2015 Sep 28. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2015.1087503

[91] Tell D., et al. (2014) Day-to-day dynamics of associations between sleep, napping, fatigue, and the cortisol diurnal rhythm in women diagnosed as having breast cancer.

[92] Tell D., et al. (2014) Day-to-day dynamics of associations between sleep, napping, fatigue, and the cortisol diurnal rhythm in women diagnosed as having breast cancer.

[93] Fei-Hsiu Hsiao., et al. (2009) The self-perceived symptom distress and health-related conditions associated with morning to evening diurnal cortisol patterns in outpatients with major depressive disorder

[94] Grossi G., et al. (2015) Stress-related exhaustion disorder–clinical manifestation of burnout? A review of assessment methods, sleep impairments, cognitive disturbances, and neuro-biological and physiological changes in clinical burnout.

[95] Leese G., et al. (1996) Short-term night-shift working mimics the pituitary-adrenocortical dysfunction in chronic fatigue syndrome.

[96] Ponzio, E., et. al., Qi-gong training reduces basal and stress-elicited cortisol secretion in healthy older adults, European Journal of Integrative Medicine, Volume 7, Issue 3, May 2015, Pages 194-201

[97] Thirtalli, J., et. al., Cortisol and antidepressant effects of yoga, Indian J Psychiatry. 2013 Jul; 55(Suppl 3): S405–S408. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.116315

[98] Turakitwanakan W., et. al., (2013) Effects of mindfulness meditation on serum cortisol of medical students., J Med Assoc Thai. 2013 Jan;96 Suppl 1:S90-5.

[99] McQuaid, et al., (2016) Relations between plasma oxytocin and cortisol: The stress buffering role of social support, Neurobiol Stress. 2016 Jun; 3: 52–60, Published online 2016 Jan 30. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2016.01.001

[100] Park BJ., et al., (2010) The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ Health Prev Med. 2010 Jan;15(1):18-26. doi: 10.1007/s12199-009-0086-9.